I wrote this upon the passing of Dr. John Hope Franklin in 2009. It was printed in ‘The Carrboro Citizen.’

“The open mind of John Hope Franklin.” The life of John Hope Franklin has now been celebrated, as it should, in publications across the world. Adding substantively to those august acknowledgments and outpourings of genuine affection is beyond this commentary. Still, Dr. Franklin did touch my life as historian and as activist.

Dr. Franklin’s work informs my classroom in many ways. In teaching courses on the history of the American South, I loan out my copy of ‘The Free Negro in North Carolina, 1790-1860’ pretty much every semester. This semester, an adult student, an African-American woman born in Alabama into a family of sharecroppers, has it and is applying it to research she is doing for a final paper. She had first heard of Dr. Franklin in a video we viewed, ‘Dr. Frank: The Life and Times of Frank Porter Graham’ as he spoke of how Graham had never worried about how people might view his associations, instead seeking out diverse ways of seeing in order to further deepen his own. Dr. Franklin appears in the video a tall and formal man carefully choosing his words so as to most precisely portray the life of the man in question. Graham (most known for being president of

#UNC 1930-1949) took much heat over his associations but never let that stop him from seeking the exchange of ideas and the concomitant progress they might bring to bear on the world.

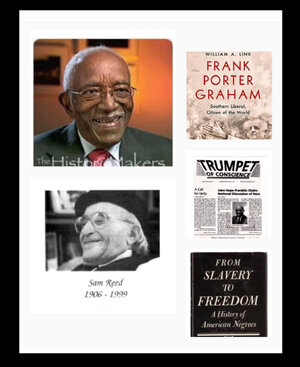

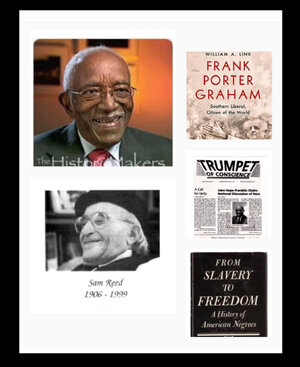

I met Dr. Franklin through Sam Reed. Sam was Ukraine-born, a tireless worker for equal rights and a communist. At the age of 80, Sam founded the newsletter “The Trumpet of Conscience” and in his retirement here in (Durham) North Carolina worked tirelessly to bridge racial divides. Scholars like William Chafe, James David Barber, and Dr. Franklin were persuaded and cajoled by Sam Reed to write for “The Trumpet.” In 1995, I worked on various projects sponsored by Sam and the publication. When Dr. Franklin spoke at the 10th anniversary of Sam’s publication in 1996, he referred to himself as a “Friend of The Trumpet.” He was also a friend of Sam Reed’s and much in the spirit of Frank Porter Graham, John Hope Franklin also sought associations that others might shun. After all, Sam was a known communist who had, during the days of the most stringent McCarthyism, served time for expressing himself in ways unpopular to the powers that be.

Dr. Franklin’s life was also one of articulating ideas unpopular with those that run society. That was, in fact, the essence of his history. And Dr. Franklin’s research was deep and full, impeccably documented and unassailable as to his interpretation of sources, assuring that his work could never be successfully attacked on grounds of scholarship. Historical actors that challenge the prevailing thought assail hegemony. We can all take a great cue from Dr. Franklin in both remaining open to radical voices and minding our own pronouncements for their accuracy. Positive change needs such scholars and thinkers and hard workers as Dr. Franklin, Sam Reed, and Frank Porter Graham. That to me is the inspiration of Dr. Franklin. [End 2009 Article]

In 2021 I added the following (edited slightly in 2023)…

I think that homage holds up relatively well. I still find that trio of scholar-activists admirable and worthy of emulation.

UNC has had a rough row to hoe in the years since 2009, most recently over the badly bungled mis-hiring of journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones. Geeta N. Kapur has written about the university and race in, "To Drink from the Well: The Struggle for Racial Equality at the Nation's Oldest Public University.” In a July 7, 2021 article in “Facing South” online magazine she recounted the following about Frank Porter Graham: “In a keynote speech he delivered to an integrated audience of 1,500 people in Birmingham, Alabama in 1938 at the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, an organization committed to improving social justice, civil rights, and instituting electoral reforms to repeal the poll tax in the South, President Graham said, ‘The black man is the primary test of American democracy and Christianity.’

President Graham was also a fierce defender of academic freedom. In his inauguration speech on Nov. 11, 1931, he told us: “Along with culture and democracy, must go freedom. Without freedom there can be neither true culture nor real democracy. Without freedom there can be no university. Freedom in a university runs a various course and has a wide meaning. In the university should be found the free voice not only for the unvoiced millions but also for the unpopular and even the hated minorities. Its platform should never be an agency of partisan propaganda but should ever be a fair forum of free opinion.”.�

https://www.facingsouth.org/.../voices-uncs-troubled...

Historical context is important. In its fullest realization it can liberate. It can also, if manipulated or half-recognized give cover where none is due. John Hope Franklin, Frank Porter Graham, and Sam Reed were born, respectively, in 1915, 1886, and 1906. They each saw clearly the wrongness in both the racism rampant during their lives and in the half-remembering of it, proving that clear vision for the generations that went before us was, indeed, possible, albeit perhaps rarer than it should have been.

[Added 2024] Of late the assault on Dr. Graham’s ‘Free Voice in The University’ as political forces gather mandates on What may be taught and How. Florida serves as a Model it appears and men and women grasping the levers of power and clutching purse strings in North Carolina want no more discussion of ideas unpopular to them. My Deddy said “The hit dog always yells,” and the truth of past and present threaten to strike them squarely. They and their lackeys betray themselves. It seems that they could not care less. They don’t respect the work lives of the Franklins, Grahams, or Reeds of our past and would rather erase them. The battle is on. Holding actions look like stalemates but consider the alternative.

[Added 2025] Updating this message to note that at this time the North Carolina General Assembly is in deep consideration of the passage of the NC REACH Act (So dangerously fully titled as ‘Reclaiming College Education on America’s Constitutional Heritage’) — it having gone to the Senate Committee on Rules and Operations on March 17 — This bill which would control the testing, weight of grading, and the nature of the way material related to the Foundations of American Democracy, a program already mandated by the legislature through the UNC System Board of Governors, will be studied while requiring copies of course syllabi at each of the 17 campuses of the UNC system and the Community Colleges. You can read the bill here:

https://webservices.ncleg.gov/ViewBillDocument/2025/1704/0/DRS45133-MT-7A I have no doubt that Dr. Graham would have been in Raleigh fighting this breach of Academic Freedom tooth and nail. Dr. Franklin would have joined him.

On September 22, 1947 John Hope Franklin (1915-2009) published ‘From Slavery to Freedom,’ the formative survey text even today in AFAM History. This link from the NC Department of Cultural Resources celebrates that historical work.

https://www.ncdcr.gov/.../scholaractivist-john-hope...

Dr. Franklin was the President of the

#OAH,

#AHA, &

#SHA and spent most of his career in N.C., finishing at

#Duke. The John Hope Franklin Center for Interdisciplinary and International Studies is located there. He passed away on March 25, 2009. He was 94 years old. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1995. John Hope Franklin passed on at the age of 94 on March 25, 2009.