Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

"As in All Hitler's Speeches, Lies Abound" 9/20/39: This Date in History

- Thread starter donbosco

- Start date

- Replies: 1K

- Views: 152K

- Off-Topic

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 4,372

Even the youngest historian needs to be a rubbernecker. There’s no turning away from the past because it’s bad. I had learned about the Pandemic of 1918-1919 reading history books as a boy. For the most part, it had always been wrapped into the narrative of WW1 in those sources. Morbid topics need exploring and I have done my share. The very first article that I published focused on a typhus epidemic in the Guatemalan highlands and disputes over treatment and burials. It was titled, “A Cry at Daybreak: Death, Disease, and Defence of Community in a Highland Ixil-Mayan Village.” In keeping with the theme, I’ve always loved cemeteries and have spent many hours wandering through them imagining the stories, good and bad, buried there.

Some years ago we lived next door to New Garden Burial Grounds in Greensboro and I walked through it at least twice everyday. A very young Delilah and I often enjoyed perusing the markers. As my daughter and I passed through in the mornings, me heading to work at Guilford College, and she to Day Care at ‘A Child’s Garden’ at New Garden Friends Meeting, one memorial, that of Jayne Fentress Kemper Lamb, (1918-2005) - pictured below - always received a ‘Hello Miss Jayne’ from her.

As for me, I usually saluted the grave of poet Randall Jarrell (marker also pictured below) most known for his gruesome poem, ‘The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.’

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose. ~ R. Jarrell

&&&&&&@&&&&&&

The variety of decorations for recollecting the Dead always amaze me. Western North Carolina has some unique ones but so too does my favorite northern cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, just north of New York City. Likewise El Cemeterio General in Guatemala City is filled with marvels. The western highland Mayan city of Quetzaltenango is a good rival and the burial ground there is chock full of legends and haunting tales.

So often flags, carved symbols, and left-behinds reveal facts of the life, and the death, of those interred. For years I’ve also been on the lookout for First Pandemic tombstones during my wanderings. In particular for the years 1918-1919 there are more of the sad little reclining lambs that remember babies and toddlers. The ‘Blue Death’ of 1918-19 took many more infants — and with a sobering rapidity — than did our modern novel virus.

I was fortunate to survive our recent epidemic and I suppose there will have been plenty of new sod turned and monuments erected across the state, the nation, and the planet for me to identify and inventory. Should those who passed stubbornly unvaccinated bear some special marking as did the babies from the first so that we may know, at a glance, just where they stood and how they fell? I know historians would appreciate that kind of tombstone ‘heads-up.’

#OTD (September 19) 1918 “Spanish Flu” hit #Wilmington — within 1 week 400 were sick. 1918-19 saw 20% of the state infected. “The official death toll from the Spanish flu in North Carolina was around 13,700. Relative to today’s population, that would be about 56,000 fatalities.” See here: Historic Outbreak: Spanish Flu on NC Coast (on May 10, 2023 they stopped counting the death toll for NC for the 21st century Covid-19 Pandemic at 29,059 —See here: (Archive) COVID-19 Cases and Deaths Dashboard | NC COVID-19 )

In the early 20th century pandemic the sickness and death overwhelmed North Carolina’s State Health Care, itself a brand new idea and branch of government, and charity was pushed beyond its limits. See here our #OTD, September 19, 1918, when the virus was first detected in Wilmington: The Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918

Another cemetery worth a visit is Bonaventure Cemetery in Savannah, GA. Johnny Mercer and Conrad Aiken are buried there. The live oaks and Spanish moss give it an eerie feeling.

Even the youngest historian needs to be a rubbernecker. There’s no turning away from the past because it’s bad. I had learned about the Pandemic of 1918-1919 reading history books as a boy. For the most part, it had always been wrapped into the narrative of WW1 in those sources. Morbid topics need exploring and I have done my share. The very first article that I published focused on a typhus epidemic in the Guatemalan highlands and disputes over treatment and burials. It was titled, “A Cry at Daybreak: Death, Disease, and Defence of Community in a Highland Ixil-Mayan Village.” In keeping with the theme, I’ve always loved cemeteries and have spent many hours wandering through them imagining the stories, good and bad, buried there.

Some years ago we lived next door to New Garden Burial Grounds in Greensboro and I walked through it at least twice everyday. A very young Delilah and I often enjoyed perusing the markers. As my daughter and I passed through in the mornings, me heading to work at Guilford College, and she to Day Care at ‘A Child’s Garden’ at New Garden Friends Meeting, one memorial, that of Jayne Fentress Kemper Lamb, (1918-2005) - pictured below - always received a ‘Hello Miss Jayne’ from her.

As for me, I usually saluted the grave of poet Randall Jarrell (marker also pictured below) most known for his gruesome poem, ‘The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.’

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose. ~ R. Jarrell

&&&&&&@&&&&&&

The variety of decorations for recollecting the Dead always amaze me. Western North Carolina has some unique ones but so too does my favorite northern cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, just north of New York City. Likewise El Cemeterio General in Guatemala City is filled with marvels. The western highland Mayan city of Quetzaltenango is a good rival and the burial ground there is chock full of legends and haunting tales.

So often flags, carved symbols, and left-behinds reveal facts of the life, and the death, of those interred. For years I’ve also been on the lookout for First Pandemic tombstones during my wanderings. In particular for the years 1918-1919 there are more of the sad little reclining lambs that remember babies and toddlers. The ‘Blue Death’ of 1918-19 took many more infants — and with a sobering rapidity — than did our modern novel virus.

I was fortunate to survive our recent epidemic and I suppose there will have been plenty of new sod turned and monuments erected across the state, the nation, and the planet for me to identify and inventory. Should those who passed stubbornly unvaccinated bear some special marking as did the babies from the first so that we may know, at a glance, just where they stood and how they fell? I know historians would appreciate that kind of tombstone ‘heads-up.’

#OTD (September 19) 1918 “Spanish Flu” hit #Wilmington — within 1 week 400 were sick. 1918-19 saw 20% of the state infected. “The official death toll from the Spanish flu in North Carolina was around 13,700. Relative to today’s population, that would be about 56,000 fatalities.” See here: Historic Outbreak: Spanish Flu on NC Coast (on May 10, 2023 they stopped counting the death toll for NC for the 21st century Covid-19 Pandemic at 29,059 —See here: (Archive) COVID-19 Cases and Deaths Dashboard | NC COVID-19 )

In the early 20th century pandemic the sickness and death overwhelmed North Carolina’s State Health Care, itself a brand new idea and branch of government, and charity was pushed beyond its limits. See here our #OTD, September 19, 1918, when the virus was first detected in Wilmington: The Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 4,372

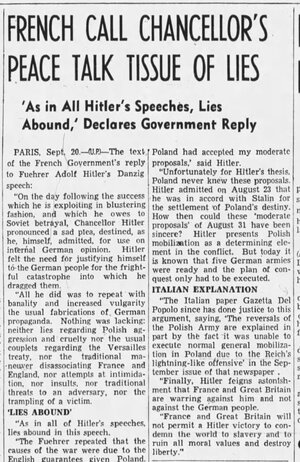

Article clipped from Oakland Tribune

Clipping found in Oakland Tribune published in Oakland, California on 9/20/1939.

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 4,372

The Danzig Speech referred to above.

The Avalon Project : Address by Adolf Hitler - September 1, 1939

The Avalon Project : Address by Adolf Hitler - September 1, 1939

Share: