Appendix IV — On the Sensuous Conditions of Comradely Contradiction

It is an error of bourgeois philosophy to treat emotion as a realm wholly divorced from production, to exile it to the private sphere, where it can be commodified as sentiment or isolated as pathology. But just as labor produces not only commodities but also relations of domination and dependency, so too does intellectual labor, shared in the crucible of revolutionary praxis, produce something surplus to mere thought: the affective infrastructure of comradeship.

In the case of the author and his co-conspirator, Friedrich Engels—whose contribution to this project is immeasurable and whose beard is rivaled only by the dialectic—this surplus grew not linearly, but dialectically, through years of collaboration, exile, poverty, and theoretical struggle. It would be idealism to describe our relation as mere friendship, and vulgar materialism to reduce it to utility. Rather, what emerged was a contradictory unity: an emotional mode of production, determined not only by shared ideology, but by mutual recognition through struggle.

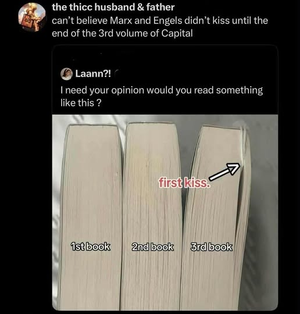

On the evening of the third of September—precisely at the moment the concept of abstract labor was being re-evaluated in light of Hegel's

Science of Logic—a fissure opened in the superstructure of the study. Not literal, but perceptible nonetheless. The category of “comrade” began to show its insufficiency. As we debated the extent to which surplus value could be abstracted without the abstraction of the laborer himself, there was a pause—longer than theory would justify.

It was not speech that followed, but a gesture—hesitant, historic. A hand rested, not by accident, atop mine. This act, though minor in empirical terms, was total in its phenomenological consequence. Here, one saw the collapse of two false binaries: intellect and emotion, public and private. For what is praxis, if not the material actualization of contradiction?

And so: the kiss—neither premeditated nor impulsive, but the inevitable synthesis of thesis and antithesis. It was not erotic in the bourgeois sense (that is, reducible to consumption), but revolutionary: a defiance of alienation through contact. The moment was charged with the entirety of our mutual project. The proletariat was not absent from that room; they were immanent in it, just as the collapse of private property is already latent in capital.

To speak of love is dangerous in a society still governed by exchange. But if love is the overcoming of separation—of the subject’s isolation under capital—then let it be stated clearly: love, like revolution, is a matter not of idealism, but of necessity.

History does not proceed through stillness, but rupture. And here, in the midst of critique, a rupture had occurred—not a deviation from the project, but its most intimate extension. Let the bourgeoisie mock what they do not understand. We will seize not only the means of production, but the means of relation. Let the future be built upon both.

—

K. Marx, London, 1867

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com