Presumably Chatgpt's summary of Super's op. Inspired by your use of AI, here is Gemini's thoughts on Super's op (which, in my opinion, does not do a good job highlighting the merits, while spending a shit-ton of time on its critique):

Summary

The provided text argues that democracy, in practice, operates as a

Prisoner's Dilemma game, making it inherently susceptible to sub-optimal outcomes. The author begins by defining

game theory as a mathematical model for multi-actor competition, using a simple husband-wife recreation example to illustrate how different payoffs lead to different outcomes. The text then introduces the Prisoner's Dilemma, a specific game where individual self-interest leads to a worse collective outcome. The classic scenario of two prisoners is explained, where both confessing (defecting) is the dominant strategy for each, even though remaining silent (cooperating) would yield a better result for both. The author then applies this model to democracy, asserting that actions like

gerrymandering and

winner-take-all electoral systems are the inevitable result of this "defecting" strategy. The author concludes that because the "cooperate" strategy is always dominated by the "defect" strategy, states cannot be relied upon to fix issues like gerrymandering on their own, and the Supreme Court was therefore foolish to defer to them.

Merits

- Clear Analogy: The author uses a clear and relatable analogy of the husband-wife recreation to introduce the concept of game theory and payoffs. This makes the subsequent, more complex examples easier to understand for a lay audience.

- Strong Central Thesis: The core argument—that democracy can be viewed through the lens of a Prisoner's Dilemma—is a powerful and thought-provoking idea. It provides a useful framework for understanding why political actors often engage in self-serving behaviors that harm the collective good.

- Identifies a Real Problem: The text correctly identifies the real-world political problems of gerrymandering and the winner-take-all electoral system, which are widely recognized as issues that contribute to political polarization and a lack of representative government.

Flaws

1. Fundamental Misrepresentation of Game Theory

The author's very foundation is flawed, starting with the attribution of game theory to John Nash. While Nash's work on

Nash Equilibrium was revolutionary, he did not invent game theory. That honor goes to

John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, who laid the groundwork in their 1944 book

Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. The author's subsequent application of the theory is similarly flawed. The husband-wife example is not a generic "simple game," but a specific type called a

Battle of the Sexes, a coordination game where both players want to cooperate but disagree on the best outcome. The author's claim that its outcomes are "impossible to predict" is false; game theory predicts that the couple will settle on one of the two

pure-strategy Nash equilibria (both at the football game or both at the opera), or a mixed-strategy equilibrium where they randomize their choices. This reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of the very concepts being used to build the argument.

2. The Prisoner's Dilemma Is Inapplicable to Real-World Politics

The author's central thesis rests on a flawed application of the Prisoner's Dilemma to politics. The classic Prisoner's Dilemma assumes a

single interaction between two actors who cannot communicate. Real-world politics is a complex,

iterated game involving multiple actors who are in constant communication and have a long history of interactions. In iterated games, cooperation is a very real possibility. Strategies like

tit-for-tat, where a player cooperates on the first move and then mimics the opponent's previous move, have been shown to be highly effective at promoting cooperation over time. The author's dismissal of cooperation as "strictly dominated" is only true for a single-shot game, rendering the entire conclusion invalid for a multi-round political system. The very existence of international treaties, independent redistricting commissions, and voluntary campaign finance reforms directly contradicts the author's deterministic view that defection is the only rational choice.

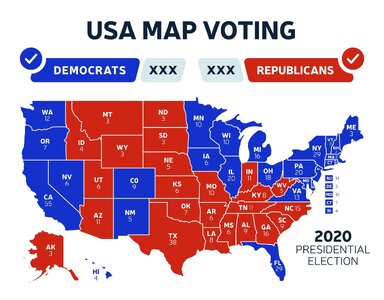

3. Contradictory and Factually Incorrect Claims about Elections

The author makes several glaring factual errors that undermine the credibility of the argument. The claim that "every state has winner-take-all assignment of electoral votes" is immediately contradicted by the author's own mention of Maine and Nebraska. Furthermore, the author's analysis of how a proportional system would work in a state like North Carolina is deeply flawed. The author seems to confuse a net gain in power for a party with a net change in the state's total electoral votes. A proportional system is designed to more accurately reflect the statewide vote, not to create a "net" loss of electoral votes for the state. Instead of one party getting all 16 votes, they might get 9, while the other gets 7. The state's total number of electoral votes remains 16. The author's notion that this "makes no sense" is a subjective judgment that ignores the purpose of such a reform—to increase voter representation and fairness.

4. Shallow and Inaccurate Critique of the Supreme Court

The author's criticism of the Supreme Court's ruling on gerrymandering is simplistic and misrepresents the legal reasoning. The Court in

Rucho v. Common Cause didn't say that states "could take care of it." Instead, it ruled that

partisan gerrymandering claims were

non-justiciable, meaning they presented a political question that the federal courts were not equipped to resolve because there was no "manageable standard" for them to apply. The Court did not endorse gerrymandering; it merely stated that it was a problem to be solved by the political process, not by the judiciary. The author's assertion that California and New York are "backpedaling" is also an exaggeration. California's independent redistricting commission, for instance, remains a functional model that has been widely praised and emulated by others, demonstrating that political cooperation to solve this problem is possible. The author's claim that a state's "cooperate strategy is

strictly dominated by defect" is a gross overstatement that is contradicted by the existence of states that have successfully reformed their redistricting processes.