- Messages

- 2,369

I could be wrongCould it have been earlier? Dook closed the place in 1980.

It was a Psych Hospital in Asheville Was after 1980 for sure???

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

I could be wrongCould it have been earlier? Dook closed the place in 1980.

I could be wrong

It was a Psych Hospital in Asheville Was after 1980 for sure???

I remember there was a patient there-long term-he had something crazy like a $1,000 bill he would show folks He was an heir to the Tabsco Sauce fortuneI mispoke...the link says that they "closed the unit in the 1980s" not IN 1980. I remember that Lee Smith's son Josh was there in the 1980s. She wrote a book about the hospital during the Zelda years and in an interview she mentioned that she knew the place personally because of that reason. Shelf Awareness for Readers for Tuesday, October 15, 2013

Lee Smith’s Guests on Earth is set in Highland Hospital in the ‘30’s and ‘40’s. A fictionalized Zelda Fitzgerald is in the book.

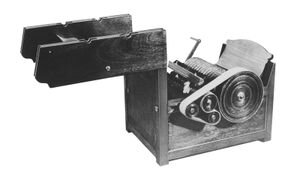

Eli tney gained its name from the inventor of the cotton gin, Eli Whitney. The reasoning for this was because there was once a cotton gin located in the community, but has been gone for many years now. Eli Whitney was once home to a school as well, but it too closed and was later demolished. The school's gymnasium was left standing and now serves as a community center.[

Eli tney gained its name from the inventor of the cotton gin, Eli Whitney. The reasoning for this was because there was once a cotton gin located in the community, but has been gone for many years now. Eli Whitney was once home to a school as well, but it too closed and was later demolished. The school's gymnasium was left standing and now serves as a community center.[Had to be 2021? The whole thing was canceled the night of the UNC loss to Syracuse in 2020 …

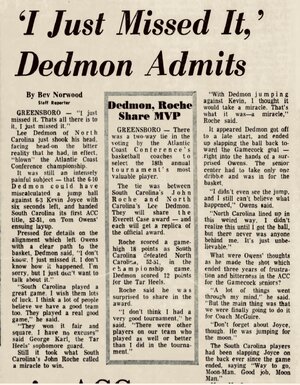

Dedmon's first cousin is one of my dorm mates with whom still get together and we text during games. Lee was a nice guy and became a school principal and superintendent in Charlotte for many years.This is an #OTD for March 13, 1971. I’m posting it here because I very much appreciate the folks who visit this thread.

There have been some crushing Down moments - that’s what happens when you truly care. The Highs can also be incredibly, well, high, too. “Sportsball” isn’t everyone’s ’cup of tea’ - as an academic of that I am acutely aware. Once after in the aftermath of a huge Carolina victory and the subsequent “Taking of Franklin Street” I was at a campus lecture. The subject has been long forgotten but an exchange that I overheard there will be with me forever. A “sportsball-hater,” strident and feeling confident in their stance commented with unmistakable disdain to a well-known faculty leftist’ “I can’t believe all the commotion in the streets after that ballgame the other night.” Expecting confirmation from the professor the young scholar looked expectantly, sneaking a sideways glance at me, also well-known as a “sportsball-lover.” To my eternal gratitude lefty Prof replied: “It was a great win. To see such joy and solidarity in people lifts my heart.”

This past ACC semifinal loss to Duke was a Giant Down in the Great Cycle of Joy and Solidarity. It’ll make the next Great High better. My first memory in that Ever-Lasting Roundabout came almost exactly 54 years ago - March 13, 1971 was the night that 6-3 South Carolina Gamecock Kevin Joyce went up against 6-10 Tar Heel Lee Dedmon in a jumpball with 3.5 seconds - Dedmon “missed it” and in a moment the exactness of which remains in dispute the enemy Tom Owens grabbed the tipped ball and scored a lay up - sending USC to the NCAA tournament and UNC home in defeat.

Despite averaging 12 points and 8 rebounds per game on a 26–6 (11–3 ACC) squad - one that took the championship of the consolation National Invitational Tournament - Dedmon has forever been remembered by all but the most understanding of The Faithful as the guy who lost the ACC Tournament to the hateful Gamecocks. And believe me, the enmity felt for South Carolina in those days in North Carolina arenas, dens, and taverns - even places of worship - eclipsed anything felt today between Blue, Red, or Black and Gold fanbases.

Dedmon’s Coach, Dean Smith, stood beside him as did his teammates - indeed, they pulled together and played their way to that NIT Crown - and I know at least one fan, albeit only 12 years old, who did forgive and forget, and remembers that season and that team for so much more. Steve Previs, George Karl, Bill Chamberlain, Dennis Wuycik, and Lee Dedmon. Evidence might be that there is nary a pause nor a hesitation as those names from 50 plus years past spill forth with ease. Indeed, Dave Chadwick, Donn Johnston, Kim Huband, Craig Corson, and Bill Chambers come to mind pretty easily as well. That crew of Tar Heels were my undisputed heroes in the rural, small-town, #DeepChatham County world. And so they remain as do all those young men who have donned the Sky Blue and sweated and bled for Carolina.

They’re my team every year through thick and thin. Ups and Downs, Highs and Lows. As for mistakes, a great philosopher once said…”recognize it, admit it, learn from it, forget it.”