Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

This Date in History

- Thread starter nycfan

- Start date

- Replies: 698

- Views: 13K

- Off-Topic

- Messages

- 2,362

With Tonnettesdb,

Did Chatham County schools come to Memorial Hall once a year (likely Grades 3/4 through 8/9) to hear the NC Symphony perform?

Chapel Hill-Carrboro Schools did; but, that’s a really short bus ride from each school.

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 3,142

BTW - while we didn’t have any, it would have made a lot of sense if we’d’ve had a few short buses for some of the folks that I came up with.db,

Did Chatham County schools come to Memorial Hall once a year (likely Grades 3/4 through 8/9) to hear the NC Symphony perform?

Chapel Hill-Carrboro Schools did; but, that’s a really short bus ride from each school.

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 3,142

Missed this one by a day...A connection with a day of infamy.

#OTD (May 13, 1846).

He must have been our greatest orator in a time of great orators. A moral compass as the immorality of slavery poisoned the land, Frederick Douglass stood tall in contrast to the duplicitous, slave-trading President James K. Polk, whose unsuitability for the job I have been reminded of frequently throughout the morass of trumpism. In Polk’s case the lies set up The Civil War. And what of Our future? On This Day in 1846 US (NC) Pres James K. Polk declared war on Mexico. A war to acquire territory into which slavery could expand --over half of the Mexico was taken by force. In 1848 Frederick Douglass laid bare the treachery in an editorial. https://www.historyisaweapon.com/.../northstareditorialwa...

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

To see a related entry on our Map of Blood and Fire, click here.

To Read the rest of the speech go here: "The War with Mexico" | North Star Editorial (January 21, 1848)

Or You Can Listen Here as Benjamin Bratt delivers Douglass' Address:

#OTD (May 13, 1846).

He must have been our greatest orator in a time of great orators. A moral compass as the immorality of slavery poisoned the land, Frederick Douglass stood tall in contrast to the duplicitous, slave-trading President James K. Polk, whose unsuitability for the job I have been reminded of frequently throughout the morass of trumpism. In Polk’s case the lies set up The Civil War. And what of Our future? On This Day in 1846 US (NC) Pres James K. Polk declared war on Mexico. A war to acquire territory into which slavery could expand --over half of the Mexico was taken by force. In 1848 Frederick Douglass laid bare the treachery in an editorial. https://www.historyisaweapon.com/.../northstareditorialwa...

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

From aught that appears in the present position and movements of the executive and cabinet—the proceedings of either branch of the national Congress,—the several State Legislatures, North and South—the spirit of the public press—the conduct of leading men, and the general views and feelings of the people of the United States at large, slight hope can rationally be predicated of a very speedy termination of the present disgraceful, cruel, and iniquitous war with our sister republic. Mexico seems a doomed victim to Anglo Saxon cupidity and love of dominion. The determination of our slaveholding President to prosecute the war, and the probability of his success in wringing from the people men and money to carry it on, is made evident, rather than doubtful, by the puny opposition arrayed against him. No politician of any considerable distinction or eminence, seems willing to hazard his popularity with his party, or stem the fierce current of executive influence, by an open and unqualified disapprobation of the war. None seem willing to take their stand for peace at all risks; and all seem willing that the war should be carried on, in some form or other. If any oppose the President's demands, it is not because they hate the war, but for want of information as to the aims and objects of the war. The boldest declaration on this point is that of Hon. John P. Hale, which is to the effect that he will not vote a single dollar to the President for carrying on the war, until he shall be fully informed of the purposes and objects of the war. Mr. Hale knows, as well as the President can inform him, for what the war is waged; and yet he accompanies his declaration with that prudent proviso. This shows how deep seated and strongly bulwarked is the evil against which we contend. The boldest dare not fully grapple with it.From Voices of A People's History, edited by Zinn and Arnove

To see a related entry on our Map of Blood and Fire, click here.

To Read the rest of the speech go here: "The War with Mexico" | North Star Editorial (January 21, 1848)

Or You Can Listen Here as Benjamin Bratt delivers Douglass' Address:

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 3,142

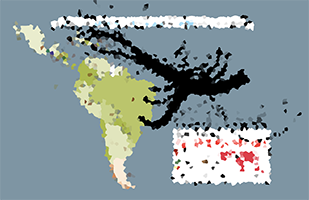

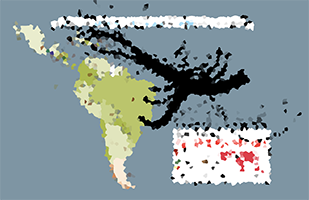

The Jamestown colony has become intertwined in our political polarization of late since that early settlement figures most prominently in “The 1619 Project.” The year 1619 is important because it is marked as the year enslaved Africans were brought to that first English colonial settlement in North America. As a Historían of Latin America what the early Spanish invaders were doing has been part of my study and teaching.

That a Spanish imperial expedition attempted to colonize in South Carolina in 1526 and failed because of a rebellion and resistance of enslaved Africans accompanying them, aided by local indigenous allies, needs to be acknowledged as part of our national narrative. Without that admission we are not telling the full story of Africans, Native Americans, nor of Hispanics in this country (see the work of Linda Heywood and John Thornton, ‘Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660’).

Interestingly (Tellingly?), most references to that early Spanish settlement of San Miguel Guadalpe leave off, or at best, downplay, the alliance of enslaved Africans and Native Americans of April 22, 1526 that thwarted that initial effort planting chattel enslavement of Africans on the mainland. (Great example here in the ‘South Carolina Encyclopedia’: https://www.scencyclopedia.org/.../san-miguel-de-gualdape/ )

Nevertheless, it is notable to remember that #OnThisDay (May 14) in 1607 the 1st permanent English settlement in North America was chartered at a place they named Jamestown, Virginia — “We landed all our men,” George Percy wrote ‘which were set to worke about [i.e., on] the fortification, and others some to watch and ward as it was convenient.’” https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/may-14

That a Spanish imperial expedition attempted to colonize in South Carolina in 1526 and failed because of a rebellion and resistance of enslaved Africans accompanying them, aided by local indigenous allies, needs to be acknowledged as part of our national narrative. Without that admission we are not telling the full story of Africans, Native Americans, nor of Hispanics in this country (see the work of Linda Heywood and John Thornton, ‘Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660’).

Interestingly (Tellingly?), most references to that early Spanish settlement of San Miguel Guadalpe leave off, or at best, downplay, the alliance of enslaved Africans and Native Americans of April 22, 1526 that thwarted that initial effort planting chattel enslavement of Africans on the mainland. (Great example here in the ‘South Carolina Encyclopedia’: https://www.scencyclopedia.org/.../san-miguel-de-gualdape/ )

Nevertheless, it is notable to remember that #OnThisDay (May 14) in 1607 the 1st permanent English settlement in North America was chartered at a place they named Jamestown, Virginia — “We landed all our men,” George Percy wrote ‘which were set to worke about [i.e., on] the fortification, and others some to watch and ward as it was convenient.’” https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/may-14

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 3,142

More on that First Rebellion of Enslaved Africans in the Americas here:

From The Washington Post, August 23, 2019 by Ciara Torres-Spelliscy…

As the New York Times noted recently in a blockbuster issue of its magazine, African slavery started in America in 1619. That's true, but only if you ignore a significant chapter of American history: the Spanish-Afro-American historical experience in Florida.

In many parts of the United States, including Florida, Texas and New Mexico, Spanish speakers arrived first. That matters not just for historical accuracy. It also helps reframe the current rhetorical and political upheaval that surrounds immigration from Spanish-speaking nations to the United States, by reminding us how Spanish-speaking black slaves helped build the nation that we now have.

There is a tendency of many people who write the history of America to have a view of the world centered on Jamestown and the Anglo American experience. When history fixates on the 13 original American colonies, the rest of the map, including Florida, seems to fall away. But it's worth expanding that picture to include Spanish-occupied territory in what is now the United States.

When we consider those lands, we see that slavery actually dates back a full century before 1619. Slavery in Florida reveals how a multinational slave trade built on personal greed and white supremacy forced Africans and African Americans to build North American wealth in which they would not be able to share. Then, adding insult to injury, these early black slaves were erased from the standard narrative of American history.

In 1511 Spain's King Ferdinand instructed his subjects in the New World to "get gold, humanely, if you can, but at all hazards, [to] get gold." Spanish explorers heeded their king's call. Florida was named by Juan Ponce de León, who claimed it for Spain in 1513 when he was searching in vain for the Fountain of Youth and gold.

Spanish empire-building in the era was driven in part by desire for greater territory. Conquests in Mexico by Hernan Cortés in 1521 and in Peru by Francisco Pizarro between 1531 and 1534 had also produced an insatiable lust for gold that fueled the treasure hunt in the New World. Ponce de León, however, had to settle for merely claiming the land of Florida for Spain, since there was neither gold nor mythical fountains to be found.

On the heels of Ponce de León's claiming Florida, the Spanish empire tried to create settlements in its new territory. For example, in 1526 another Spanish explorer, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, tried to establish a Spanish settlement at San Miguel de Gualdape in what was then La Florida (the current Georgia or South Carolina coast.) The Ayllón group included both Spaniards and African slaves who were brought as mining and agricultural laborers. But the settlement collapsed. First, some of the Spaniards mutinied against Ayllón. Then the African slaves burned down the mutineers' housing and went to live with Native Americans in the area.

While the historical record on early slavery in Florida is thin, scholars have uncovered the ways in which it was endorsed and exploited by the Spanish crown, while being challenged and resisted by the very slaves forcibly brought across the Atlantic through the slave trade. In 1539, slavery arrived in present-day Florida when the slave trader and Spanish explorer Hernando DeSoto attempted to establish a permanent settlement and claim more territory for Spain.

We know very little about the black slaves with DeSoto. A letter from Spain's King Charles V dated April 20, 1537, gave DeSoto permission to take 50 Africans, a third of them female, to Florida. According to historian Jane Landers, DeSoto's slaves included both Moors from Northern Africa and sub-Saharan Africans. Many of them deserted him to live with the Native Americans in Florida. We know that DeSoto abandoned some black slaves during his expeditions, including two with known names. One named Robles, who apparently was Christian, was left at Coosa, Ala., because he was too ill to walk. And another slave named Johan Biscayan was left at Ulibahali in present-day Georgia.

Over the succeeding decades, black slaves helped build the Spanish colonial infrastructure, including most notably St. Augustine, Fla., in 1565, the oldest city in the United States. As historian Edwin Williams reported in a 1949 article that uncovered this history, "Negro slavery was first introduced into what is now the United States . . . many years before the 'first' Negroes were landed at Jamestown, Virginia."

The history of slavery was shaped by the battle between Spanish authorities keen on exploiting African labor and African resistance, resulting in documented episodes of fleeing and arson like the ones noted above.

But there were also short periods in which Spanish authorities offered slaves freedom if they professed the Catholic faith. During the mid-1700s the Spanish king allowed a town of freed blacks to flourish outside of St. Augustine as part of the struggle against Protestantism in the New World. This town was sometimes referred to as Pueblo de Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, Fort Moosa or the Negro Fort. It existed from 1738 until 1763, when the British took over Florida and all of the black free residents of Fort Moosa fled, mostly to Cuba. Today known as Fort Mose, it is part of a historic state park.

Florida came under British rule thanks to the treaty ending the French and Indian War. And it was then that the plantation slavery of the American colonial South began to take root. On the eve of the Revolutionary War, the population in Florida was roughly 1,000 white people and 3,000 black slaves. Spanish rule returned over the period from 1784 to 1821 as the result of battles during the American Revolution that allowed Spain to recapture territory.

The United States purchased Florida in 1821. By the time it became a state in 1845, roughly half its population was black and enslaved, though there were a few hundred free blacks as well. The 1845 Florida constitution ensured that emancipation would remain illegal, even giving the state the power to forbid the entrance of new free blacks from other states.

While this history has largely been lost, American abolitionists certainly did not ignore slavery in Florida. In 1844, abolitionist Johnathan Walker was caught trying to free seven slaves from Florida. He was convicted and sentenced to stand in the pillory and to be branded on the hand with the letters S.S. (for slave stealer). Similarly, according to Julia Floyd Smith, in 1848 a group of "slave stealers" was caught in Tallahassee and hanged.

Sometimes Florida slaves would steal themselves, as Frederick Douglass once put it. In a daring escape in 1854, 12 slaves escaped Florida by boat, making it to the Bahamas. This fight over slavery would continue over the next two decades, with newspapers routinely promising bounties for the return of runaway Florida slaves.

The New York Times did a great service in placing black history in a central place in our narrative of the past. But it left out a chapter. The year 1619 is certainly important. But so too is the more complicated historical narrative of slavery in Florida that predates it, and that the state of Florida officially recognized only in 2008.

Just like the British colonists to the north, the Spanish imperial project also fed the demand for forced labor with Africans, though with the carrot dangled that they might gain freedom by adopting the king's religion. Perhaps a greater appreciation of this history of cultural and racial complexity, which includes blacks and whites speaking English, Spanish and other languages as America was developed and explored, would assist us in having a more nuanced discussion about it means to be an "American" today — because from the start, America was multiracial and polyglot.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outl...ts-not-actually-when-slavery-america-started/

From The Washington Post, August 23, 2019 by Ciara Torres-Spelliscy…

As the New York Times noted recently in a blockbuster issue of its magazine, African slavery started in America in 1619. That's true, but only if you ignore a significant chapter of American history: the Spanish-Afro-American historical experience in Florida.

In many parts of the United States, including Florida, Texas and New Mexico, Spanish speakers arrived first. That matters not just for historical accuracy. It also helps reframe the current rhetorical and political upheaval that surrounds immigration from Spanish-speaking nations to the United States, by reminding us how Spanish-speaking black slaves helped build the nation that we now have.

There is a tendency of many people who write the history of America to have a view of the world centered on Jamestown and the Anglo American experience. When history fixates on the 13 original American colonies, the rest of the map, including Florida, seems to fall away. But it's worth expanding that picture to include Spanish-occupied territory in what is now the United States.

When we consider those lands, we see that slavery actually dates back a full century before 1619. Slavery in Florida reveals how a multinational slave trade built on personal greed and white supremacy forced Africans and African Americans to build North American wealth in which they would not be able to share. Then, adding insult to injury, these early black slaves were erased from the standard narrative of American history.

In 1511 Spain's King Ferdinand instructed his subjects in the New World to "get gold, humanely, if you can, but at all hazards, [to] get gold." Spanish explorers heeded their king's call. Florida was named by Juan Ponce de León, who claimed it for Spain in 1513 when he was searching in vain for the Fountain of Youth and gold.

Spanish empire-building in the era was driven in part by desire for greater territory. Conquests in Mexico by Hernan Cortés in 1521 and in Peru by Francisco Pizarro between 1531 and 1534 had also produced an insatiable lust for gold that fueled the treasure hunt in the New World. Ponce de León, however, had to settle for merely claiming the land of Florida for Spain, since there was neither gold nor mythical fountains to be found.

On the heels of Ponce de León's claiming Florida, the Spanish empire tried to create settlements in its new territory. For example, in 1526 another Spanish explorer, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, tried to establish a Spanish settlement at San Miguel de Gualdape in what was then La Florida (the current Georgia or South Carolina coast.) The Ayllón group included both Spaniards and African slaves who were brought as mining and agricultural laborers. But the settlement collapsed. First, some of the Spaniards mutinied against Ayllón. Then the African slaves burned down the mutineers' housing and went to live with Native Americans in the area.

While the historical record on early slavery in Florida is thin, scholars have uncovered the ways in which it was endorsed and exploited by the Spanish crown, while being challenged and resisted by the very slaves forcibly brought across the Atlantic through the slave trade. In 1539, slavery arrived in present-day Florida when the slave trader and Spanish explorer Hernando DeSoto attempted to establish a permanent settlement and claim more territory for Spain.

We know very little about the black slaves with DeSoto. A letter from Spain's King Charles V dated April 20, 1537, gave DeSoto permission to take 50 Africans, a third of them female, to Florida. According to historian Jane Landers, DeSoto's slaves included both Moors from Northern Africa and sub-Saharan Africans. Many of them deserted him to live with the Native Americans in Florida. We know that DeSoto abandoned some black slaves during his expeditions, including two with known names. One named Robles, who apparently was Christian, was left at Coosa, Ala., because he was too ill to walk. And another slave named Johan Biscayan was left at Ulibahali in present-day Georgia.

Over the succeeding decades, black slaves helped build the Spanish colonial infrastructure, including most notably St. Augustine, Fla., in 1565, the oldest city in the United States. As historian Edwin Williams reported in a 1949 article that uncovered this history, "Negro slavery was first introduced into what is now the United States . . . many years before the 'first' Negroes were landed at Jamestown, Virginia."

The history of slavery was shaped by the battle between Spanish authorities keen on exploiting African labor and African resistance, resulting in documented episodes of fleeing and arson like the ones noted above.

But there were also short periods in which Spanish authorities offered slaves freedom if they professed the Catholic faith. During the mid-1700s the Spanish king allowed a town of freed blacks to flourish outside of St. Augustine as part of the struggle against Protestantism in the New World. This town was sometimes referred to as Pueblo de Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, Fort Moosa or the Negro Fort. It existed from 1738 until 1763, when the British took over Florida and all of the black free residents of Fort Moosa fled, mostly to Cuba. Today known as Fort Mose, it is part of a historic state park.

Florida came under British rule thanks to the treaty ending the French and Indian War. And it was then that the plantation slavery of the American colonial South began to take root. On the eve of the Revolutionary War, the population in Florida was roughly 1,000 white people and 3,000 black slaves. Spanish rule returned over the period from 1784 to 1821 as the result of battles during the American Revolution that allowed Spain to recapture territory.

The United States purchased Florida in 1821. By the time it became a state in 1845, roughly half its population was black and enslaved, though there were a few hundred free blacks as well. The 1845 Florida constitution ensured that emancipation would remain illegal, even giving the state the power to forbid the entrance of new free blacks from other states.

While this history has largely been lost, American abolitionists certainly did not ignore slavery in Florida. In 1844, abolitionist Johnathan Walker was caught trying to free seven slaves from Florida. He was convicted and sentenced to stand in the pillory and to be branded on the hand with the letters S.S. (for slave stealer). Similarly, according to Julia Floyd Smith, in 1848 a group of "slave stealers" was caught in Tallahassee and hanged.

Sometimes Florida slaves would steal themselves, as Frederick Douglass once put it. In a daring escape in 1854, 12 slaves escaped Florida by boat, making it to the Bahamas. This fight over slavery would continue over the next two decades, with newspapers routinely promising bounties for the return of runaway Florida slaves.

The New York Times did a great service in placing black history in a central place in our narrative of the past. But it left out a chapter. The year 1619 is certainly important. But so too is the more complicated historical narrative of slavery in Florida that predates it, and that the state of Florida officially recognized only in 2008.

Just like the British colonists to the north, the Spanish imperial project also fed the demand for forced labor with Africans, though with the carrot dangled that they might gain freedom by adopting the king's religion. Perhaps a greater appreciation of this history of cultural and racial complexity, which includes blacks and whites speaking English, Spanish and other languages as America was developed and explored, would assist us in having a more nuanced discussion about it means to be an "American" today — because from the start, America was multiracial and polyglot.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outl...ts-not-actually-when-slavery-america-started/

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 3,142

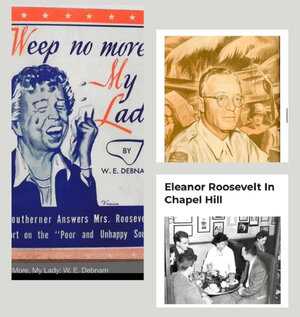

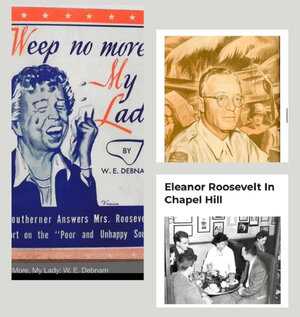

Some little remembered but significant NC (Regional? National?) History.

Waldemar Eros Debnam was a North Carolina predecessor to Jesse Helms in being a Right-Wing Name-Caller and Media Firebrand. He was before my time but I suspect that his ‘work’ helped to establish some of the more prevalent wrong-headed ways-of-seeing plaguing the state at present (as is the case w/Helms). That he took potshots at Eleanor Roosevelt and spouted Revisionist Redeemer History on the radio, in print, and via imagery while feigning faux southern gentility is no surprise. The Right Wing has always sought to appeal to the lowest sentiments of humanity and obfuscate trollishly - we see the continuance of that in the trumpist GOP today through Election Denial and Insurrectionist Celebration and General Prevarication (lying). The legacy of men like Debnam is the likes of Marjorie Taylor Green and Madison Cawthorn but even, and perhaps worse, Sean Hannity and the entire FAUX Network.

#OTD (May 15) in 1950 N.C. Pundit W.E, Debnam published ‘Weep No More, My Lady,’ attacking Eleanor Roosevelt for critiquing poverty in the state by stating that “she was ‘not so sure that there are not signs of poverty and unhappiness that will gradually have to disappear if that part of the nation is going to prosper.’” Debnam countered that The Region’s Weak Economics were due to General Sherman’s Campaign, The Civil War, and Reconstruction. He also wrote that Race Relations were better in The South than in The North.

Debnam was born in Snow Hill (Greene County) in 1897. His father was a teacher who became a small town newspaper publisher. His mother took over management of the paper when her husband died. W.E. worked there from a young age. After attending UNC he worked at newspapers in Washington D.C. , Danville, and Norfolk, Virginia. Finding radio to his taste he migrated to Raleigh and WPTF-AM. During World War II he reported from the Pacific Theater and received wide acclaim for his interviews with soldiers there.

In the 1950s he dabbled in politics, winning a seat on the Raleigh City Council that he held for two years. In 1955 he published a very successful booklet titled, “Then My Old Kentucky Home, Good Night!” which condemned the Brown v Board of Education decision and the order to desegregate school. In that publication he termed himself a “Neverist” in regard to the integration. He added, “…every tradition of this great land of ours, every tenet of our democracy, every precept upon which our Republic is founded demands that we stand up and fight with every weapon at our command to see to it that integration is not forced upon a single white or Negro child in all the South.” Debnam continued, asserting that “the ultimate goal of school integration is racial amalgamation and ‘the destruction of both the white and Negro race.’” (Shreveport LA, The Times, July 19, 1955) Debnam died in 1968 - he was still working the news - at that time at WITN-TV in Washington, NC.

Raleigh Broadcaster Tangled with Former First Lady

Waldemar Eros Debnam was a North Carolina predecessor to Jesse Helms in being a Right-Wing Name-Caller and Media Firebrand. He was before my time but I suspect that his ‘work’ helped to establish some of the more prevalent wrong-headed ways-of-seeing plaguing the state at present (as is the case w/Helms). That he took potshots at Eleanor Roosevelt and spouted Revisionist Redeemer History on the radio, in print, and via imagery while feigning faux southern gentility is no surprise. The Right Wing has always sought to appeal to the lowest sentiments of humanity and obfuscate trollishly - we see the continuance of that in the trumpist GOP today through Election Denial and Insurrectionist Celebration and General Prevarication (lying). The legacy of men like Debnam is the likes of Marjorie Taylor Green and Madison Cawthorn but even, and perhaps worse, Sean Hannity and the entire FAUX Network.

#OTD (May 15) in 1950 N.C. Pundit W.E, Debnam published ‘Weep No More, My Lady,’ attacking Eleanor Roosevelt for critiquing poverty in the state by stating that “she was ‘not so sure that there are not signs of poverty and unhappiness that will gradually have to disappear if that part of the nation is going to prosper.’” Debnam countered that The Region’s Weak Economics were due to General Sherman’s Campaign, The Civil War, and Reconstruction. He also wrote that Race Relations were better in The South than in The North.

Debnam was born in Snow Hill (Greene County) in 1897. His father was a teacher who became a small town newspaper publisher. His mother took over management of the paper when her husband died. W.E. worked there from a young age. After attending UNC he worked at newspapers in Washington D.C. , Danville, and Norfolk, Virginia. Finding radio to his taste he migrated to Raleigh and WPTF-AM. During World War II he reported from the Pacific Theater and received wide acclaim for his interviews with soldiers there.

In the 1950s he dabbled in politics, winning a seat on the Raleigh City Council that he held for two years. In 1955 he published a very successful booklet titled, “Then My Old Kentucky Home, Good Night!” which condemned the Brown v Board of Education decision and the order to desegregate school. In that publication he termed himself a “Neverist” in regard to the integration. He added, “…every tradition of this great land of ours, every tenet of our democracy, every precept upon which our Republic is founded demands that we stand up and fight with every weapon at our command to see to it that integration is not forced upon a single white or Negro child in all the South.” Debnam continued, asserting that “the ultimate goal of school integration is racial amalgamation and ‘the destruction of both the white and Negro race.’” (Shreveport LA, The Times, July 19, 1955) Debnam died in 1968 - he was still working the news - at that time at WITN-TV in Washington, NC.

Raleigh Broadcaster Tangled with Former First Lady

- Messages

- 1,162

Was Debnam the guy who played WITHney the Hobo on the afternoon kids show? If so, he was GREAT! I loved WITHney the Hobo. ETA: It sounds like Debnam was already a clown, so playing WITHney the Hobo wouldn't have been much of a stretch for him.. . .. Debnam died in 1968 - he was still working the news - at that time at WITN-TV in Washington, NC. . . ..

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 3,142

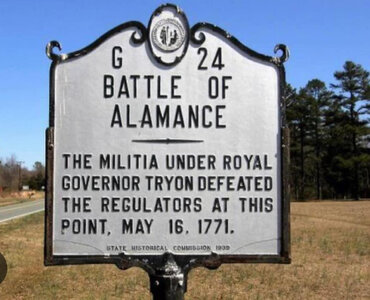

Honesty is certainly intimately intertwined with Morality. So too is the sense of fairness and equity. The former stands as indisputable to me — you either Lie or you Tell the Truth. What you believe yourself to be doing is certainly important to be sure but the inveterate Liar deserves no Quarter — The Liar for Profit and Gain, no Mercy. 254 years ago today in Piedmont NC folk stood against both an economy and a set of government officials who were knowingly, and immorally deeply dishonest and believed their birthright, as elites in a hierarchical society, made that reality well and good. Believing themselves an unassailable ruling class, these Agents of the British Crown, most notably Orange County and Hillsborough Town Commissioner Edmund Fanning, had, beginning around 1760, consistently and increasingly, been cheating the working class farmers in the backcountry in a rigged judicial and tax system.

The farmers believed in a moral economy and as their government strayed from that principle their support for it waned. By 1766 resistance in the rural Piedmont backcountry peaked, as did elite corrupt comportment. Marjoleine Kars has written of the duplicity of the King’s men in Orange and of how the historic order of British society was by the 1760s an ill-fit for the outlands in her book, ‘“Breaking Loose Together,: The Regulator Rebellion in Pre-Revolutionary North Carolina,: https://uncpress.org/.../9780807.../breaking-loose-together/.

Ideas about equal treatment before the law and in market dealings, most born of radical Protestant sects — i.e., studied Christian Ethics — were winning the day on the frontier. What traditional elites believed should be the arrangement of society was breaking down in the frontier spaces of North Carolina.

Details Matter. #OTD (May 16) in 1771 The Battle of Alamance was fought between Militia standing for King George III and Frontiersmen angry over corrupt, dishonest government. English Imperial Governor William Tryon journeyed from New Bern and led 1100 troops equipped with artillery against 2000 unorganized and Ill-equipped ‘Regulators.’ No doubt many of the 3100 involved that day were confused or misinformed. Duty to a monarch had been the way for time immemorial and was an allegiance not easily left aside. But a new sense of human and civil rights was also growing stronger and stronger in the borderland. Those sentiments came into contention in the North Carolina colony between 1766 and 1771 and is known as The War of The Regulation.

On May 16, 1771 the King’s forces won the Day and took the field. 9 died on each side. This battle ended the resistance — for a time. There is more here: https://www.ncdcr.gov/.../gov-tryon-takes-regulators...

I have long thought that our state motto, “Esse Quam Videri/To Be Rather Than To Seem” connected with The Regulator sense of fairness in its clear rejection of the inequity and affectation that typified men such as Fanning and Tryon and instead embraced the honest simplicity of the farmer.

Unfortunately I have seen some evidence that some of our modern traitors and insurrectionists wrongly imagine themselves descendants of these sincere Tar Heel fighters. Such an analogy is fundamentally flawed and deeply wrongheaded since those heroes of 1771 fought AGAINST lies. The blood spilled fighting corruption in Orange and Alamance and Chatham in 1771 warrants no connection to the Sedition of January 6, 2021 as the latter was perpetrated ON BEHALF OF LIES. They’d like to own this history but truth precludes it. This is exactly why the story must be told in full modern context.

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 3,142

17th May #TheDayInHistory

#OTD (May 17) in 1957, Dr #MartinLutherKingJr, delivered his “Give Us the Ballot” speech during the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom demonstration in front of the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, DC.

#MLK said, "Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights. Give us the ballot, and we will no longer plead to the federal government for passage of an anti-lynching law; we will by the power of our vote write the law on the statute books of the South and bring an end to the dastardly acts of the hooded perpetrators of violence.

Give us the ballot, and we will transform the salient misdeeds of bloodthirsty mobs into the calculated good deeds of orderly citizens. Give us the ballot, and we will fill our legislative halls with men of goodwill and send to the sacred halls of Congress men who will not sign a “Southern Manifesto” because of their devotion to the manifesto of justice..."

#OTD (May 17) in 1957, Dr #MartinLutherKingJr, delivered his “Give Us the Ballot” speech during the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom demonstration in front of the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, DC.

#MLK said, "Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights. Give us the ballot, and we will no longer plead to the federal government for passage of an anti-lynching law; we will by the power of our vote write the law on the statute books of the South and bring an end to the dastardly acts of the hooded perpetrators of violence.

Give us the ballot, and we will transform the salient misdeeds of bloodthirsty mobs into the calculated good deeds of orderly citizens. Give us the ballot, and we will fill our legislative halls with men of goodwill and send to the sacred halls of Congress men who will not sign a “Southern Manifesto” because of their devotion to the manifesto of justice..."

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 3,142

And of course, #OTD in 1954.

#OTD (May 17, 1954) in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the US Supreme Court voted unanimously that “Segregation of students in public schools violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, because separate facilities are inherently unequal.”

Imagine - a UNANIMOUS decision. Imagine today’s SCOTUS rendering such a verdict. A SCOTUS that makes of a president a king above the law would not - could not - bring such justice. So watch the trump administration’s case now before the court challenging birthright citizenship. Why? Because striking that down would give courts leeway to narrow the scope of other clauses in the Constitution and most specifically in the 14th Amendment — like Equal Protection and Due Process ((See 5th Amendment too) — by redefining, i.e., shrinking, who is “entitled” to those protections. States or Congress could be the arbiter of citizenship in a post-birthright citizenship United States. A core promise of the 14th Amendment is that all people are equal under the law but weakening would strike at every group that has relied on the 14th Amendment for protection—racial minorities, women, LGBTQ+ people, immigrants, the disabled… All would find their rights under threat.

Right here. Right now. We are living Niemöller’s quotation? “First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew.”

#OTD (May 17, 1954) in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the US Supreme Court voted unanimously that “Segregation of students in public schools violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, because separate facilities are inherently unequal.”

Imagine - a UNANIMOUS decision. Imagine today’s SCOTUS rendering such a verdict. A SCOTUS that makes of a president a king above the law would not - could not - bring such justice. So watch the trump administration’s case now before the court challenging birthright citizenship. Why? Because striking that down would give courts leeway to narrow the scope of other clauses in the Constitution and most specifically in the 14th Amendment — like Equal Protection and Due Process ((See 5th Amendment too) — by redefining, i.e., shrinking, who is “entitled” to those protections. States or Congress could be the arbiter of citizenship in a post-birthright citizenship United States. A core promise of the 14th Amendment is that all people are equal under the law but weakening would strike at every group that has relied on the 14th Amendment for protection—racial minorities, women, LGBTQ+ people, immigrants, the disabled… All would find their rights under threat.

Right here. Right now. We are living Niemöller’s quotation? “First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew.”

Last edited:

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 3,142

17th May #TheDayInHistory

#OTD (May 17) in 1957, Dr #MartinLutherKingJr, delivered his “Give Us the Ballot” speech during the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom demonstration in front of the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, DC.

#MLK said, "Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights. Give us the ballot, and we will no longer plead to the federal government for passage of an anti-lynching law; we will by the power of our vote write the law on the statute books of the South and bring an end to the dastardly acts of the hooded perpetrators of violence.

Give us the ballot, and we will transform the salient misdeeds of bloodthirsty mobs into the calculated good deeds of orderly citizens. Give us the ballot, and we will fill our legislative halls with men of goodwill and send to the sacred halls of Congress men who will not sign a “Southern Manifesto” because of their devotion to the manifesto of justice..."

Martin Luther King was a bit overly optimistic in his “Give Us the Ballot” speech 68 years ago.

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 3,142

Fast, loud cars, slightly jacked up with ‘Mag’ Wheels & White Letter Tires were a fact of life in 1970s North Carolina. The parking lots of 1-A and 2-A small town and crossroads high schools across the state were a combo Pitstop and Gun Shop in those days. Souped up Impalas and TransAms and gun-rack fitted pick ups made up a big part of the lifestyle of a significant chunk of the local folk, the first category mainly young men and the second spanning generations.

That sparsely populated landscape was dotted by small asphalt islands and oases centered on sacred gasoline rather than the traditional water that served the night-time hours. Illegal beer made up the other venerated liquid — gas and spirits — a country cocktail and not one without its associated tragedies.

Crossroads that bore historically buried names like #Bonlee or #Bennett, #HarpersCrossroads or #BearCreek and sported not much more than a filling station/country store — no incorporation but maybe a sign — attracted cliques and halfway-gangs that gathered after-midnight and Southern Rock anthems like ‘Green Grass and High Tides’ and ‘Midnight Rider’ filled the late late evening air. By ‘74 CB Radios added to the fuss and fuzz and tied together the rural racers and revelers in “Smokey” thwarting networks that nicely foreshadowed our cell and text-connected world of today.

And boys and young men did race. Indeed, I knew more than one girl that tore up the road too.

It is a wonder more didn’t die on those narrow, shoulderless roads. A few did and a lot more ended up sideways in cornfields and cow pastures. Down home daredevils were heroes in their herd and the triumphs of NASCAR greats like Petty, Allison, Earnhardt, and Yarborough were good backdrop for the all-important local pecking order. And The Look was as important as the Speed. Car Culture was a life for some and The Race was bigger than State-Carolina for quite a few.

#OTD (May 18) in 1947, 10,000 saw #FontyFlock win the 1st race held at North Wilkesboro Speedway @Nwilkesboroswy. Dubbed ‘The House That Junior Built,’ the 5/8 Mile Oval Stadium grew to hold 60K by the last NASCAR race there in ‘96 (won by Jeff Gordon). Moonshine Connections Abound. North Wilkesboro and the Roots of NASCAR

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 3,142

On This Day in 1959 "Kansas City" hit Number One on the Pop Charts. It was performed by Wilbert Harrison (1929-1994) of Charlotte. The Video of "Kansas City" sets Harrison up as the coolest of the cool.

Really interesting audience pan at the t 1:26 mark.

“Kansas City”

Harrison's 1969 semi-hit, “Let’s Work Together” (Later released by “Canned Heat” -- There's a good chance that you've heard their version)

His Remarkable Momma’s obit

Article clipped from The Charlotte Observer

Really interesting audience pan at the t 1:26 mark.

“Kansas City”

Harrison's 1969 semi-hit, “Let’s Work Together” (Later released by “Canned Heat” -- There's a good chance that you've heard their version)

His Remarkable Momma’s obit

Article clipped from The Charlotte Observer

Share: