- Messages

- 2,174

Elon forgot his child/human shield:

Interesting that he doesn't seem nearly so concerned about his child when he's in a secured area...

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

Elon forgot his child/human shield:

Homophones aside, the notion that Apple wouldn’t invest in America except for Trump policies is ludicrous on its face.

Good move mods. Honestly I'm doing my best to not become subhuman and put myself on the level of Elon and those who revel in his contemptuous nature.Since they want to bring the word back so much I’m going start referring to them as r*****licans.

Mod note: as a teacher with numerous students whom have intellectual disabilities, we won’t be saying the r-word around here. Thanks.

“… Musk himself has recently tried to associate himself with the Clinton effort: “What @DOGE is doing is similar to Clinton/Gore Dem policies of the 1990s,” he posted on his social platform X, using his acronym for the effort in charge of the cuts, the Department of Government Efficiency.

But the Reinventing Government project was nearly the opposite of the abrupt, chaotic Musk effort, say those who ran it or watched it unfold. It was authorized by bipartisan congressional legislation, worked slowly over several years to identify inefficiencies and involved federal workers in re-envisioning their jobs.

“There was a tremendous effort put into understanding what should happen and what should change,” said Max Stier, president of the Partnership for Public Service, which seeks to improve the federal workforce. “What is happening now is actually taking us backwards.” …”

“… There is also a concern that some US embassy positions that are actually filled by CIA officers under cover may now be at risk of being revealed — potentially angering the host nation and exposing companies or endangering CIA assets who are known to have met with past occupants of the role.How Trump’s government-cutting moves risk exposing the CIA’s secrets

“The CIA is conducting a formal review to assess any potential damage from an unclassified email sent to the White House in early February that identified for possible layoffs some officers by first name and last initial and could’ve exposed the roles of people working undercover, a source familiar with the matter told CNN.

That’s just one of multiple aftershocks from President Donald Trump’s push to take a jackhammer to the federal government – including the CIA. The administration’s efforts to cut the workforce and audit spending at the CIA and elsewhere threaten to jeopardize some of the government’s most sensitive work, current and former US officials familiar with internal deliberations say.

Across the river in Washington, a senior career Treasury Department official delivered a memo warning Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent that granting a 25-year-old computer engineer with Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency access to the government’s ultra-sensitive payments system risked exposing highly classified CIA payments that flow through it.

And on the CIA’s 7th floor — home to top leadership — some officers are also quietly discussing how mass firings and the buyouts already offered to staff risk creating a group of disgruntled former employees who might be motivated to take what they know to a foreign intelligence service. …”

Great analogy. I think I’ve even noticed Elon recently trying to speak with a man’s voice.

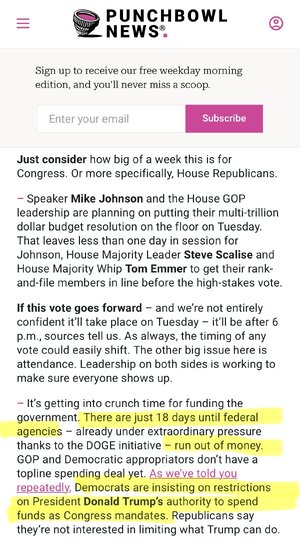

DOGE is the Theranos of Cost-Cutting

Paul Krugman: “It has always been a mistake to trust anyone promising to run the government like a business. Businesses and government agencies have very different objectives, and even genuinely great business leaders often havepoliticalwire.com

“… Now, imagine that a publicly held company were to release a statement about its earnings that was riddled with major errors — with all the errors going in the same direction, making the company’s earnings look better than they are.

What would you conclude? The answer, surely, would be to suspect that the company’s business is going very badly, but that top executives are trying desperately to hide the bad news while they sell off their own shares and possibly loot the company through sweetheart deals and so on.

… In the case of DOGE, it’s pretty clear that Musk is failing more or less comprehensively at his supposed task of saving money by eliminating waste, fraud and abuse. But he doesn’t want the public — or, more important, Donald Trump — to figure that out until he’s achieved his real objectives, which seem to involve taking effective control of large parts of the federal governmentb — particularly those parts of the federal government that are trying to regulate his enterprises and those of his tech-bro buddies.

Of course, given the indiscriminate nature of the layoffs he’s been carrying out and the devastating effect they’re having on worker morale, he may end up breaking the federal government rather than taking it over. …”

Or an ass pimple. 50-50 call.You will never convince me that Trump is not a Russian mole.

They are not mutually exclusive.Or an ass pimple. 50-50 call.