Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

2024 Presidential Election | ELECTION DAY 2024

- Thread starter nycfan

- Start date

- Replies: 8K

- Views: 338K

- Politics

quakerdevil

Distinguished Member

- Messages

- 346

I actually don't like this. A lot of people want to keep their favorite sport isolated from politics. Alabama is playing Georgia.

This is a mistake.

RockyMtnHoo

Esteemed Member

- Messages

- 515

Under normal circumstances I’d agree, but rules are different with Trump. He will not be able to let this go. I’m sure they won’t show it on the TV broadcast but the fact that she’ll embarrass him in front of 80K (75% that are probably his supporters) will get a response.I actually don't like this. A lot of people want to keep their favorite sport isolated from politics. Alabama is playing Georgia.

This is a mistake.

quakerdevil

Distinguished Member

- Messages

- 346

Under normal circumstances I’d agree, but rules are different with Trump. He will not be able to let this go. I’m sure they won’t show it on the TV broadcast but the fact that she’ll embarrass him in front of 80K (75% that are probably his supporters) will get a response.

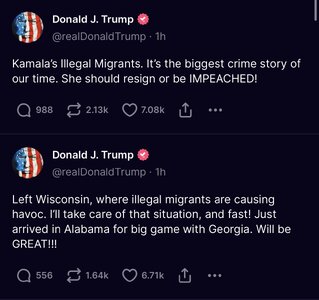

I bet they do show it actually

Bryant Denny Stadium actually holds 103,000. You are right about Trump’s response to this. He will be blasting it on social media.Under normal circumstances I’d agree, but rules are different with Trump. He will not be able to let this go. I’m sure they won’t show it on the TV broadcast but the fact that she’ll embarrass him in front of 80K (75% that are probably his supporters) will get a response.

- Messages

- 2,053

I would be very surprised if they showed it on the sports broadcast. They will show Trump a few times because he's there just like they would do it if it was Taylor Swift.

Also, Trump being there is political so I don't see how Harris doing something in response makes her the one that is crossing the politics/sports line.

Also, Trump being there is political so I don't see how Harris doing something in response makes her the one that is crossing the politics/sports line.

quakerdevil

Distinguished Member

- Messages

- 346

Just saw a Trump add here in Ohio about Kamala's love for prisoners and illegal aliens getting sex change operations

- Messages

- 41,974

See it every 15 minutes in NC.Just saw a Trump add here in Ohio about Kamala's love for prisoners and illegal aliens getting sex change operations

- Messages

- 3,200

Seems like right wingers would approve of that. Tough punishment in their minds.Just saw a Trump add here in Ohio about Kamala's love for prisoners and illegal aliens getting sex change operations

quakerdevil

Distinguished Member

- Messages

- 346

See it every 15 minutes in NC.

Internal numbers might be looking bad if they're putting the swing state ads here

Mulberry Heel

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 4,041

I just saw it for the first time. Utterly disgusting ad, and just more evidence that Trump's campaign has decided that going straight into the gutter is the only way they've got a chance to win. Attack transgenders in the most crude and vile ways possible, attack immigrants in the most crude and vile ways possible, and so on. Can equally ugly and blunt attacks on gays, lesbians, college professors, schoolteachers, blacks, etc. be far behind?Just saw a Trump add here in Ohio about Kamala's love for prisoners and illegal aliens getting sex change operations

aGDevil2k

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 4,761

Oh they've been running that one here. It's really gross and doubtful it hurtsJust saw a Trump add here in Ohio about Kamala's love for prisoners and illegal aliens getting sex change operations

Share: