They Don’t Want to Live in Lincoln’s America

Sept. 10, 2025

Listen to this article · 10:10 min

Learn more

By

Jamelle Bouie

Opinion Columnist

Although it has long since entered the pantheon of American rhetoric as one of our nation’s great orations, there was a time, however brief, when the Gettysburg Address had its critics.

The president’s words, an unnamed editorialist for The Chicago Times wrote, were “a perversion of history so flagrant that the most extended charity cannot regard it as otherwise than willful.” The Gettysburg Address is famously succinct, less a speech — that honor went to the accomplished orator Edward Everett, whose two-hour disquisition was the main event — than a short set of remarks meant simply to commemorate the occasion.

What, then, was offensive to this irate commentator? The problem, he explained, was the premise.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” President Abraham Lincoln said. This, the editorialist wrote, was nonsense. Does the Constitution, he asked, quoting those parts that allude to slavery, “dedicate the nation ‘to the proposition that all men are created equal?’” No, he said, and moreover, “Mr. Lincoln occupies his present position by virtue of this Constitution, and is sworn to the maintenance and enforcement of these provisions.”

Far from dying to consecrate a new birth of freedom, he wrote, “It was to uphold this Constitution, and the Union created by it, that our soldiers gave their lives at Gettysburg.” Lincoln was wrong — very wrong. “How dared he, then, standing on their graves, misstate the cause for which they died, and libel the statesmen who founded the government? They were men possessing too much self-respect to declare that Negroes were their equals, or were entitled to equal privileges.”

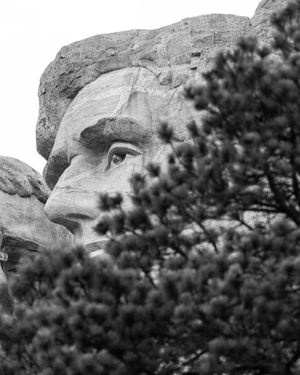

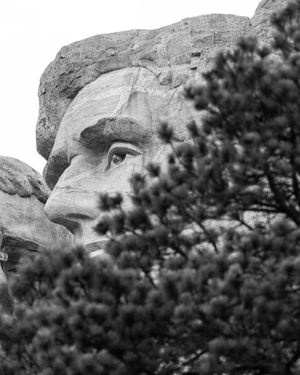

Lincoln imagined a nation dedicated to the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the aims of the founders as he understood them. His critics, from Stephen Douglas to Roger Taney to the leaders of the Confederate rebellion, said no — ours was not a society of equals but one of rigid, permanent hierarchies. Ultimately, this contest of national identity was settled by force of arms. Lincoln’s vision, backed by what was, at the time, one of the largest and

most diverse armies ever assembled on the North American continent, won the day. And his allies, charged after

his martyrdom with the great work of reconstruction, wrote this vision into the Constitution with three amendments that aimed to realize the fullness of the Declaration.

To a great extent, then, we live in Lincoln’s America as much as anyone else’s. Which makes it supremely ironic that the project of Lincoln’s partisan political descendants — the project of the modern Republican Party — is the destruction of his republic of equals in favor of a so-called homeland for a select few.

Vice President JD Vance is,

as I discussed previously, a leading light of this effort. But he is not the only Republican to carry the standard. Last week, at an annual conference for national conservatism — the illiberal right’s term of choice for its movement — Senator Eric Schmitt of Missouri

gave a speech that, in its rejection of the creedal vision of the American republic and in its embrace of an exclusionary racial nationalism, went even further than Vance has in his public statements.

“For decades, the mainstream consensus on the left and the right alike seemed to be that America itself was just an ‘idea’ — a vehicle for global liberalism,” Schmitt said. “We were told that the entire meaning of America boiled down to a few lines in a poem on the Statue of Liberty and five words about equality in the Declaration of Independence. Any other aspect of American identity was deemed to be illegitimate and immoral, poisoned by the evils of our ancestors.”

We should pause, here, to reflect on the radicalism of Schmitt’s dismissive contempt for the universalist aspirations of the American political tradition. Those “five words about equality” — “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal” — are among the most important in human history. They represent a unique moment in the story of the world, the merging of a powerful notion of universal equality with a revolutionary claim about the sources of political authority.

“For the Declaration of Independence was the first case in human history in which a single people made a national revolution on the assumption that its particular principles were, simultaneously, the universal principles which civilized men everywhere would recognize,” the historian and political philosopher Harry Jaffa wrote in what now reads as a rebuke of those who, in the present day, carry the imprimatur of his scholarly home, the Claremont Institute. “The declaration assumed,” he went on to say, “that its potential, if not its actual addresses, embraced the entire family of man.”

Put a little differently, there is a reason that those five words have been, since the day they were announced to the people of the United States, a clarion call for freedom both here and around the world. The Declaration’s promise of equality would become, in short order, a powerful touchstone for the great moral and political crusades of our nation’s history.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident,” declared the women at the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, “that all men and women are created equal.”