Interesting article about Carter and his evangelism - (behind a paywall)

www.theatlantic.com

www.theatlantic.com

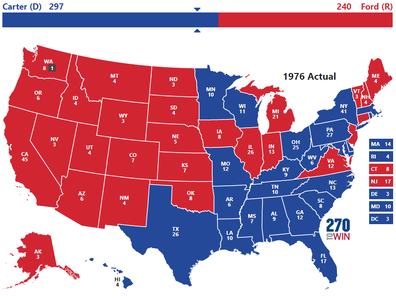

Carter captured the white evangelical vote, winning the Bible Belt (including my home state of Mississippi). An evangelical publisher released The Miracle of Jimmy Carter. His public witness was praised in Christianity Today, and he had the support of such figures as Pat Robertson and Richard John Neuhaus.

And then he went from Bible Belt icon to loathed foe of a newly energized religious-right political network in four short years—a network that was itself a kind of trans-denominational, parachurch “evangelical” project. As Randall Balmer’s biography, Redeemer, demonstrates, Carter was representative of a kind of fusion evangelicalism—strong on the need for personal conversion and sharing one’s faith with others but also politically liberal or moderate on such questions as racial justice, women’s rights, nuclear disarmament, and so on.

Carter clearly was out of step with most of his fellow white evangelicals—especially on abortion (about which he was squeamish but which he was unwilling to see legally curbed), the Equal Rights Amendment, and other “family values” questions. While identity politics at first earned Carter an unusual coalition of the South’s Black and white working-class constituencies, the accent and the testimony were eventually not enough.

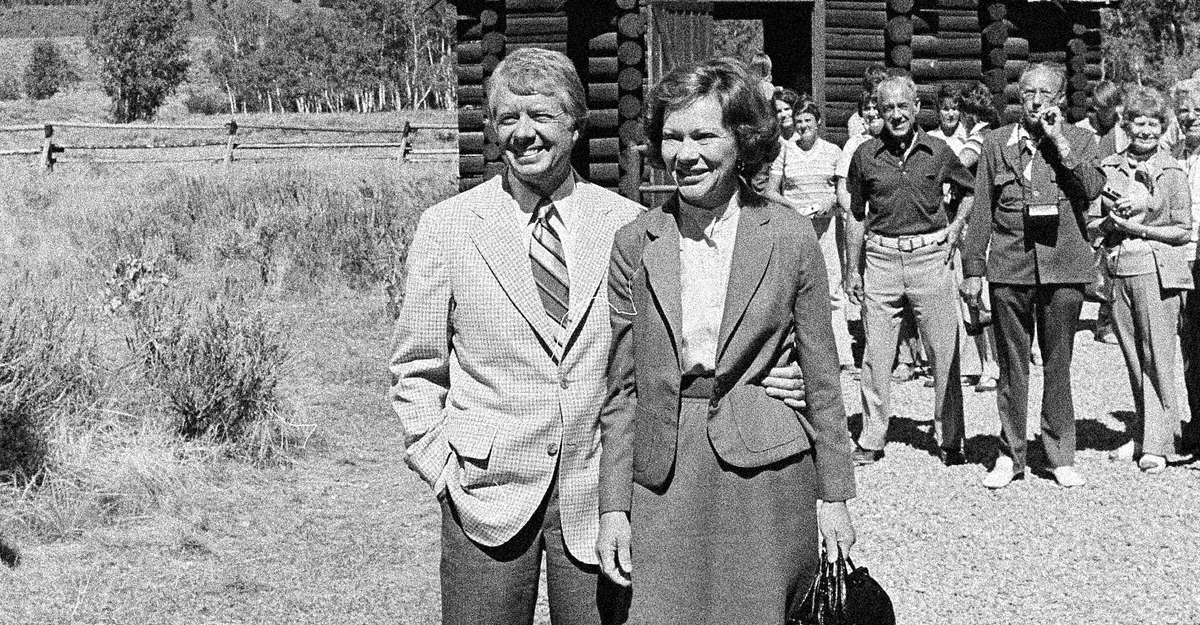

What I Learned From Praying With Jimmy Carter

“Everything has a way of coming back around,” the former president said. “What seems unstoppable and inevitable never is.”

Carter captured the white evangelical vote, winning the Bible Belt (including my home state of Mississippi). An evangelical publisher released The Miracle of Jimmy Carter. His public witness was praised in Christianity Today, and he had the support of such figures as Pat Robertson and Richard John Neuhaus.

And then he went from Bible Belt icon to loathed foe of a newly energized religious-right political network in four short years—a network that was itself a kind of trans-denominational, parachurch “evangelical” project. As Randall Balmer’s biography, Redeemer, demonstrates, Carter was representative of a kind of fusion evangelicalism—strong on the need for personal conversion and sharing one’s faith with others but also politically liberal or moderate on such questions as racial justice, women’s rights, nuclear disarmament, and so on.

Carter clearly was out of step with most of his fellow white evangelicals—especially on abortion (about which he was squeamish but which he was unwilling to see legally curbed), the Equal Rights Amendment, and other “family values” questions. While identity politics at first earned Carter an unusual coalition of the South’s Black and white working-class constituencies, the accent and the testimony were eventually not enough.