sringwal

Iconic Member

- Messages

- 1,918

This is in no way a political thread, but IMO it's interesting in a "dull men's club" way, and fuck it, I'm posting it here.

I recently learned that I am a life long sufferer of what is known as Aphantasia. This is really fucking with my head, as it explains a great deal about me.

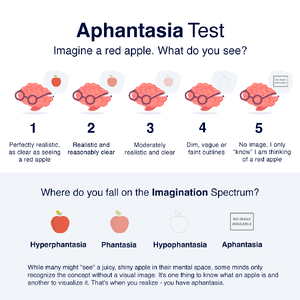

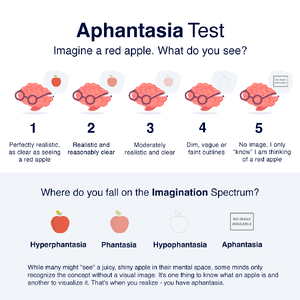

When people with aphantasia close their eyes and imagine something, we simply do not see it. My mind's eye is, essentially, blank.

Now, for years, I assumed that, when people spoke about their mind's eye, or making a movie when they read, that they were speaking in metaphor, something that my brain is prewired to do because it can't "see." I taught English at the high school level for over two decades, and was good at it, despite the fact that my experience with reading books is different from that of others (or perhaps because of its difference).

When I close my eyes and think of something, this is what I see:

I dated a girl in college who had an eidetic memory (I have no idea if having hyperphantasia and being eidetic are the same thing). She described skimming a book, taking a test (at UNC) on the material, and being able to see the words on the page that would answer the question. There was no processing of the information. She just gave the answer that was required of her, which she saw and adjusted to not be plagiarism. She also had gotten a 1590 out of 1600 on the SAT and, not surprisingly, could tell you which question she got wrong and why). I really wanted that memory until I understood how much trauma was connected to it. She was unable to let go of anything because all of her memories of everything were so incredibly vivid.

So I knew that that existed, but I assumed that everyone else's "mind's eye" was metaphorical, and not a vast spectrum, or that my mind was as abnormal as hers.

When I read, I've always placed analysis (thematic, symbolism, characterization) over plot, and never really understood why others are so concerned with things like a character's appearance, particularly when transferring from book to screen. When I read a book, I occasionally get tiny snippets of visualization, but what I generally see is just words, words, words. This is, apparently, common of people with aphantasia - who often show a strong ability to analyze in any field, but particularly math, science, and literature), because we don't have internal visual distractions. I also read quickly, and skim through long passages of narration because they are essentially useless to me.

I never really understood their purpose - if we are being honest - but now I understand that, for some people, description greatly impacts how they "see" what they read. Generally, when something like a piece of furniture gets described, I just think if it as being that particular piece of furniture until given a reason to think about it more precisely.

It also explains why memorization was difficult for me growing up. I, and other people with aphantasia tend to struggle with short term memory, particularly on the retrieval end. Throughout most of my life, I worked harder than others, but often found myself failing rote memorization.

I distinctly remember taking a test in 9th grade on Catcher in the Rye where one of the questions was "what color hat was Holden wearing?" I had no idea, because that simply wasn't something that, until then, registered when I read. The teacher was, I believe, just checking to see who had and had not read, but over the years, that moment got me more interested in visual symbolism (it was a red hunting hat, for those that are interested). The idea that anyone would simply be able to visualize Holden, wearing said hat, in their mind - had never occurred to me until recently. I would have needed to deliberately repeated "Holden Caufield wears a red hat" over and over again in my mind in order to memorize that piece of information. That, generally, is how I memorize things.

This is a video of author John Green wearing, and talking about said hat (more on John Green later).

I've also struggled with facial recognition and names for a long time. I even remember thinking, one night in middle school, how it was that we recognized people when we saw them. I wondered, at the time, if it had to do with process of elimination based on who you knew would be where and when, or had to do with the sound of their voice, or some other cues. I quickly decided that, for people that you were familiar with, it was something stronger, but I could never say, exactly, what. Oddly, I'm really great at reading body language, but that has taken decades of deliberate work on my part.

Unsurprisingly, prosopagnosia (face blindness) and aphantasia go hand in hand. When I was introduced to that concept, years ago, it was presented as looking like this:

I quickly erased that off the chart, because it isn't remotely what I see when I see someone. I believe that I "see" faces as well as anyone else (although I'm uncertain, because as with the mind's eye, I have no idea what I see vs. what someone else does), but I often struggle to be confident that, if I have only met someone a few times, they are the person that I think they are (particularly if they change their hair or appearance). That self doubt has led me to be careful to not use names (which I struggle with even when I "know" someone), and to build several cues that will help ensure that I don't make an ass of myself, or offend someone else.

I really suck at directions because I can't picture routes in my mind. It's easy for me to get lost, even in areas that I am deeply familiar with, and I often find myself taking wrong turns. Thank God for navigation tools.

Aphantasia as a concept was discovered in the late 1800s when Francis Galton conducted a study on mental imagery: Classics in the History of Psychology -- Galton (1880)

The idea sat there, but not much was done with it for the next hundred or so years.

The concept, aphantasia," is then relatively new, despite the fact that apparently at least 1% of the population suffers from it. 2015https://psyche.co/ideas/i-have-no-minds-eye-let-me-try-to-describe-it-for-you

The term didn't come into existence until 2015, although folks are starting to make up time, as there are huge implications for how we process information and communicate with others (man and machine). And, of course, how this influences dementia later in life is critical. I have a weaker autobiographical memory than others because of my condition (which is great, because I can let negative experiences with others go easier than others), but whether I'm more likely to get dementia (because my memory is already pretty shoddy) or less likely (because I make connections differently than others) is unknown at this time.

Recently, I've been researching this shit to high heaven, in part because I left the classroom to be a librarian at my school 3 years ago and then, due to district cuts, moved to the EC department. I've always been fascinated by the relationship between our minds and how we learn (In addition to being an English teacher, I was one hell of a Theory of Knowledge teacher in our school's IB program). Now that I'm working almost primarily with students who struggle in school, my focus on that has only increased (ironically, but not surprisingly, the only other person who I know who also has aphantasia is our E.C. department chair - and I've talked with a number of people in my immediate circle about my condition since then).

Being curious, I decided to look up who else has aphantasia. Ed Catmull, the co-founder of Pixar (and former head of Disney Animation Studios), is one of them, and has employed a number of artists who also have the condition (because he has it, he is "mindful" about hiring artists across the mind's visualization spectrum). Geneticist Craig Venter is another one.

(cont)

I recently learned that I am a life long sufferer of what is known as Aphantasia. This is really fucking with my head, as it explains a great deal about me.

When people with aphantasia close their eyes and imagine something, we simply do not see it. My mind's eye is, essentially, blank.

Now, for years, I assumed that, when people spoke about their mind's eye, or making a movie when they read, that they were speaking in metaphor, something that my brain is prewired to do because it can't "see." I taught English at the high school level for over two decades, and was good at it, despite the fact that my experience with reading books is different from that of others (or perhaps because of its difference).

When I close my eyes and think of something, this is what I see:

I dated a girl in college who had an eidetic memory (I have no idea if having hyperphantasia and being eidetic are the same thing). She described skimming a book, taking a test (at UNC) on the material, and being able to see the words on the page that would answer the question. There was no processing of the information. She just gave the answer that was required of her, which she saw and adjusted to not be plagiarism. She also had gotten a 1590 out of 1600 on the SAT and, not surprisingly, could tell you which question she got wrong and why). I really wanted that memory until I understood how much trauma was connected to it. She was unable to let go of anything because all of her memories of everything were so incredibly vivid.

So I knew that that existed, but I assumed that everyone else's "mind's eye" was metaphorical, and not a vast spectrum, or that my mind was as abnormal as hers.

When I read, I've always placed analysis (thematic, symbolism, characterization) over plot, and never really understood why others are so concerned with things like a character's appearance, particularly when transferring from book to screen. When I read a book, I occasionally get tiny snippets of visualization, but what I generally see is just words, words, words. This is, apparently, common of people with aphantasia - who often show a strong ability to analyze in any field, but particularly math, science, and literature), because we don't have internal visual distractions. I also read quickly, and skim through long passages of narration because they are essentially useless to me.

I never really understood their purpose - if we are being honest - but now I understand that, for some people, description greatly impacts how they "see" what they read. Generally, when something like a piece of furniture gets described, I just think if it as being that particular piece of furniture until given a reason to think about it more precisely.

It also explains why memorization was difficult for me growing up. I, and other people with aphantasia tend to struggle with short term memory, particularly on the retrieval end. Throughout most of my life, I worked harder than others, but often found myself failing rote memorization.

I distinctly remember taking a test in 9th grade on Catcher in the Rye where one of the questions was "what color hat was Holden wearing?" I had no idea, because that simply wasn't something that, until then, registered when I read. The teacher was, I believe, just checking to see who had and had not read, but over the years, that moment got me more interested in visual symbolism (it was a red hunting hat, for those that are interested). The idea that anyone would simply be able to visualize Holden, wearing said hat, in their mind - had never occurred to me until recently. I would have needed to deliberately repeated "Holden Caufield wears a red hat" over and over again in my mind in order to memorize that piece of information. That, generally, is how I memorize things.

This is a video of author John Green wearing, and talking about said hat (more on John Green later).

I've also struggled with facial recognition and names for a long time. I even remember thinking, one night in middle school, how it was that we recognized people when we saw them. I wondered, at the time, if it had to do with process of elimination based on who you knew would be where and when, or had to do with the sound of their voice, or some other cues. I quickly decided that, for people that you were familiar with, it was something stronger, but I could never say, exactly, what. Oddly, I'm really great at reading body language, but that has taken decades of deliberate work on my part.

Unsurprisingly, prosopagnosia (face blindness) and aphantasia go hand in hand. When I was introduced to that concept, years ago, it was presented as looking like this:

I quickly erased that off the chart, because it isn't remotely what I see when I see someone. I believe that I "see" faces as well as anyone else (although I'm uncertain, because as with the mind's eye, I have no idea what I see vs. what someone else does), but I often struggle to be confident that, if I have only met someone a few times, they are the person that I think they are (particularly if they change their hair or appearance). That self doubt has led me to be careful to not use names (which I struggle with even when I "know" someone), and to build several cues that will help ensure that I don't make an ass of myself, or offend someone else.

I really suck at directions because I can't picture routes in my mind. It's easy for me to get lost, even in areas that I am deeply familiar with, and I often find myself taking wrong turns. Thank God for navigation tools.

Aphantasia as a concept was discovered in the late 1800s when Francis Galton conducted a study on mental imagery: Classics in the History of Psychology -- Galton (1880)

The idea sat there, but not much was done with it for the next hundred or so years.

The concept, aphantasia," is then relatively new, despite the fact that apparently at least 1% of the population suffers from it. 2015https://psyche.co/ideas/i-have-no-minds-eye-let-me-try-to-describe-it-for-you

The term didn't come into existence until 2015, although folks are starting to make up time, as there are huge implications for how we process information and communicate with others (man and machine). And, of course, how this influences dementia later in life is critical. I have a weaker autobiographical memory than others because of my condition (which is great, because I can let negative experiences with others go easier than others), but whether I'm more likely to get dementia (because my memory is already pretty shoddy) or less likely (because I make connections differently than others) is unknown at this time.

Recently, I've been researching this shit to high heaven, in part because I left the classroom to be a librarian at my school 3 years ago and then, due to district cuts, moved to the EC department. I've always been fascinated by the relationship between our minds and how we learn (In addition to being an English teacher, I was one hell of a Theory of Knowledge teacher in our school's IB program). Now that I'm working almost primarily with students who struggle in school, my focus on that has only increased (ironically, but not surprisingly, the only other person who I know who also has aphantasia is our E.C. department chair - and I've talked with a number of people in my immediate circle about my condition since then).

Being curious, I decided to look up who else has aphantasia. Ed Catmull, the co-founder of Pixar (and former head of Disney Animation Studios), is one of them, and has employed a number of artists who also have the condition (because he has it, he is "mindful" about hiring artists across the mind's visualization spectrum). Geneticist Craig Venter is another one.

(cont)

Last edited: