te NC’s moonshine legend, a JoCo kingpin with cigars and Cadillacs By Josh Shaffer

At the height of his whiskey-soaked infamy, Percy Flowers earned over $1 million a year, enough to buy a fleet of Cadillacs and ride around hardscrabble Johnston County like an untouchable kingpin, a pistol in his pocket and a cigar on his lip. He owned more than 5,000 acres of farmland, all of it stocked with moonshine stills tucked in the woods, hidden inside tobacco barns and concealed under bluffs of the Neuse River — an operation so vast he bought sugar in 40,000-pound loads.

Flowers’ bootleg hooch enjoyed such a reputation that night clubs in Manhattan developed a code for the bartenders: four fingers wrapped around the glass meant fill ‘er up with Johnston County corn liquor. And yet, in more than 50 years as a notorious moonshiner, Flowers spent almost no time behind bars, partly because he paid off jurors and scared witnesses away from courthouses. When he did serve time, he served it for tax evasion.

But beyond his fearful image, Flowers enjoyed the reputation of a country-boy Robin Hood, showering his neighbors with money. For decades in Johnston County, churches got built and sharecroppers got fed thanks to his illicit liquor cash. Once, on a rare night in jail, he offered to buy T-bone steaks for all 164 inmates. “Largess, dash and arrogance characterize Flowers at work and at play,” wrote The Saturday Evening Post in 1958, profiling the moonshiner over six pages. “He is a cool gambler, hardy drinker and sports enthusiast. He likes to drive expensive, powerful cars, of which he customarily has three or four available, with the accelerator jammed to the floor-board.”

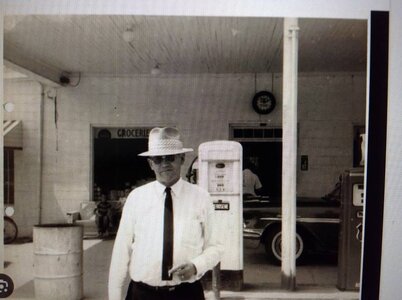

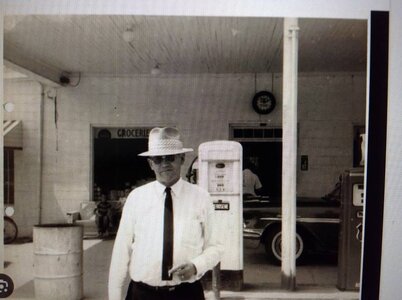

Moonshine king Percy Flowers as he appeared in a Saturday Evening Post profile in 1958.

Somehow, no book has ever told the story of Eastern North Carolina’s king of backwoods booze, an oversight that Raleigh author and folklorist Oakley Dean Baldwin has thankfully corrected. In “J. Percy Flowers, Master Distiller,” he traces the moonshine wunderkind from his first batch as a teenager in roughly 1919, when he stumbled on a still in the dark and discovered a farmhand named Lester bent over some barrels. It took a year of Lester’s teaching before Flowers could turn out a passable jug, but he managed to produce a blend that neither burned a hole through a drinker’s esophagus nor struck him blind from lead poisoning — risks of the moonshine trade.

What land Flowers could buy he leased to tenant farmers growing tobacco, cotton and corn, shielding his true source of income. What land he couldn’t buy he still managed to pull into his sphere of moonshine influence, recruiting cooperative farmers and stuffing cash inside their mailboxes in exchange for keeping mum. “While we’re dealing with a man who hasn’t had half the respect for the law a good citizen is supposed to have, he has a lot of good qualities,” a federal judge once said. “I don’t think he’s a mean man, a vicious man. If he were, he wouldn’t have as many friends. I’d like to have as many.”

Percy Flowers from Johnston County outside his country store and filling station. Courtesy of Oakley Dean Baldwin

Despite his flashy image, Flowers remained an unapologetic country boy, keeping a barn full of fighting roosters and a kennel full of fox hounds — one of which, named Coy, cost $15,000. By the Depression, Flowers was distilling liquor inside 1,500-gallon “submarine” tanks hidden underwater. He equipped his cars with short-wave radios to monitor police traffic. Every three or four months, he walked into First Citizens Bank in Smithfield with $20,000 in small bills, exchanging them for hundreds he kept locked in a safe, stacked a foot high and a foot deep. He once shot a sheriff in the bottom as he bent over a still, peppering his rear end with birdshot. He once clubbed a “revenuer” over the head with a pistol. He once threw punches at a news photographer who tried to snap his picture, telling him, “I’d give $5,000 for a shotgun. None of you better come to Johnston County.” Police once poured 348 gallons of Flowers’ whiskey down a Smithfield gutter. Yet in the courtroom, juries would deadlock. Charges got dropped. Sentences got chopped in half.

Once, Flowers got off with three days in jail when he explained that 22 sharecropping families depended on him. Another time, in 1936, when a judge sentenced him along with two brothers, he successfully argued, “Your honor, won’t be nobody to look after the farm. Will you let us go one at a time?” Another time, he followed along behind a federal agent scouring his land for a still and playfully offered to double his salary. “If you do what I tell you,” he told the revenuer, “you can retire a whole lot sooner, with a lot more money.”

The story of Johnston County liquor escapades strikes a personal note with Baldwin, who spent a long career as a Wake County sheriff’s deputy. He met Flowers in person only once during the 1970s, when he stepped inside the moonshine czar’s country store. At the time, the future deputy was still living in his native West Virginia and had only come to Garner to visit his brother-in-law. But from behind the counter, Flowers eyed Baldwin warily, asking who he was and where he came from, uttering the phrase that makes any northerner nervous: “I knew you weren’t from around here.”

Flowers died in 1982, not too many years after Baldwin clapped eyes on him. Though he had largely run out of money, he still owned more than 200 fox hounds and dozens of fighting cocks by Baldwin’s count. Few criminals he would meet in the ensuing decades could supply a book’s pages with such delicious detail.

“This story really needs to be a movie,” Baldwin said. “One day, I think it will be.” Moonshine is, of course, now bottled and sold legally — a tradition made far less glamorous by becoming respectable. But Baldwin imagines Flowers rising out of his boozy legend, reborn as a folk hero. Imagine the tourists Johnston County could pull off Interstate 95 with a Percy Flowers Moonshine Festival, complete with virtual-reality Cadillac races and rooster fights. What fun it would be to wear a souvenir wide-brimmed hat cocked at a jaunty angle, chomp on a candy cigar and sip firewater out of a fruit jar — thumbing one’s nose at a boring, straitlaced world.