LOLPete Hegseth thought he was flexing with his people. Only to find out they are not really his people. Seems like Hegseth is the one who FA FO'd today.

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Hegseth ordered hundreds of generals to meet on short notice in Virginia

- Thread starter ChapelHillSooner

- Start date

- Replies: 434

- Views: 10K

- Politics

- Messages

- 923

i have nothing to lose but my life which we are all gonna lose regardless. millions dead is nothing for the betterment of future generations. i understand completely the fat and happy attitudes of most americans....too gutless for any sacrifice whatsoever. look around...this isnt going to end happily regardless of what you want to avoid that might disrupt your entitled bubble.We know what hitting "rock bottom" looks like in this country - it was a Civil War that claimed the lives of roughly 2.5% of the population. A modern analogue to that could mean something like 9 million dead. It is absurd to call people "dumb" or "gutless" because they want to avoid that scenario. You act like we have nothing to lose, but we in fact have a whole lot to lose, especially because there's no guarantee we would come out of the other side a unified and stronger nation.

The issue is not that anyone can't imagine that horror - the issue is that anyone who welcomes such horror is insane.

- Messages

- 2,656

Eh, this type of nihilism is just a lack of principles masquerading as principles. I have lots to lose other than my life, including the lives of my children, my family and friends, and the rest of the people in my community and country; and not just their lives, but also their happiness, their education, their livelihoods, and their physical and mental health. Anyone who would cavalierly throw away the lives and happiness of their fellow citizens for some hypothetical better future that may or may not come to pass is either a fool or a psychopath. it's really no different to me than saying "what happens to this world doesn't matter because I'm going to live forever in heaven." Anyone who can type the phrase "millions dead is nothing" and really mean it is someone whose opinion I surely am not going to take seriously.i have nothing to lose but my life which we are all gonna lose regardless. millions dead is nothing for the betterment of future generations. i understand completely the fat and happy attitudes of most americans....too gutless for any sacrifice whatsoever. look around...this isnt going to end happily regardless of what you want to avoid that might disrupt your entitled bubble.

Captain Bo Sides

Active Member

- Messages

- 27

i have nothing to lose but my life which we are all gonna lose regardless. millions dead is nothing for the betterment of future generations. i understand completely the fat and happy attitudes of most americans....too gutless for any sacrifice whatsoever. look around...this isnt going to end happily regardless of what you want to avoid that might disrupt your entitled bubble.

I take it you'll be fighting for both sides?

Also, Congress had not yet passed the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878. So there was no lawful prohibition on using the military for domestic law enforcement. That is a very significant difference.I agree with this to some extent, but at least Lincoln was dealing with a true national emergency - by far the greatest emergency in American history - the violent rebellion of nearly half the states in the Union. By contrast the America Trump inherited had plenty of problems but certainly nothing approaching a national emergency of that level. These efforts to declare economic, immigration, and cultural emergencies are just complete BS. So even if one agreed with Lincoln allowing some extremely harsh violations of civil liberties during the Civil War, there simply would be no justification for using them right now.

superrific

Master of the ZZLverse

- Messages

- 10,641

And also the ranks of domestic law enforcement had been hollowed out by the war effort. And also law enforcement was nowhere near as effective back then, given that they had virtually no equipment or technology. And also law enforcement jobs were patronage positions.Also, Congress had not yet passed the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878. So there was no lawful prohibition on using the military for domestic law enforcement. That is a very significant difference.

- Messages

- 2,656

I truly hope they don’t. Their country needs them.I wonder if any of these Generals and Admirals will resign now.

- Messages

- 1,942

I sure hope that none who felt like the resignation comments were directed toward them end up resigning.I wonder if any of these Generals and Admirals will resign now.

I'd like to think that clownish/dangerous/lunatic speech may even have strengthened their resolve to stay at their posts. They saw, VIVIDLY, what the true domestic enemy looks like. I'd b e a little shocked if there weren't some behind the scenes discussion of how unhinged our ruling regime has become.I truly hope they don’t. Their country needs them.

I'm sure there are some MAGA generals, but I imagine most are just solid, ethical, conservative folks. Many may even agree with parts of the plan w/r/t readiness and standards. But they ain't stupid, and it doesn't take a genius to see how far this might be pushed.

- Messages

- 1,598

When I was in the Army, I can count on one hand the number of times I had an actual conversation with someone with a rank higher than O-4. But based on those exceeding few conversations and a few other times where I heard those of rank O-5 or above speak frankly in a setting with only a few people present, I always came away with the impression that they were smart, insightful, and knowledgeable of the current events of the day, regardless of whether those events had any impact on or relationship to their professional duties. As such, I believe that those of ranks O-5 to O-10 who are genuinely appalled by what President Trump and his lackies are doing to this country will not resign, but will feel an obligation to the oath they swore when they first joined the military to remain at their posts and do what they can, for as long as they can to remain faithful to that oath.I wonder if any of these Generals and Admirals will resign now?

gtyellowjacket

Iconic Member

- Messages

- 2,413

There's also a separate debate on Lincoln suspending habeas corpus during an insurrection, but not in a place that was actually in revolt and if that was really legal. This law was in place at the time.Also, Congress had not yet passed the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878. So there was no lawful prohibition on using the military for domestic law enforcement. That is a very significant difference.

Using the military for domestic law enforcement was legal at the time, I think the question should be if it was a good idea. It seems the Congressional leaders in 1878 did not feel like it was a good idea to let the president use the military for domestic law enforcement at the President's whim and I think they were right. It should be noted that Trump just lost a court judgment specifically related to posse comitatus when he sent the national guard into California to help with immigration enforcement.

Edit. I jumbled the habeas corpus and military law enforcement argument.

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 4,628

Upon enlisting in the United States Armed Forces, each person enlisting in an armed force (whether a soldier, Marine, sailor, airman, or Coast Guardsman) takes an oath of enlistment required by federal statute in 10 U.S.C. § 502. That section provides the text of the oath and sets out who may administer the oath:

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

§ 502. Enlistment oath: who may administer

(a) Enlistment Oath.— Each person enlisting in an armed force shall take the following oath:

Or, if enlisting in the National Guard:I, (state name of enlistee), do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; and that I will obey the orders of the President of the United States and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to regulations and the Uniform Code of Military Justice. (So help me God)."

I, (state name of enlistee), do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States and of the State of (applicable state) against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to them; and that I will obey the orders of the President of the United States and the Governor of (applicable state) and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to law and regulations. (So help me God)."

United States Armed Forces oath of enlistment - Wikipedia

donbosco

Inconceivable Member

- Messages

- 4,628

Re: Lincoln and writ of Habeas Corpus

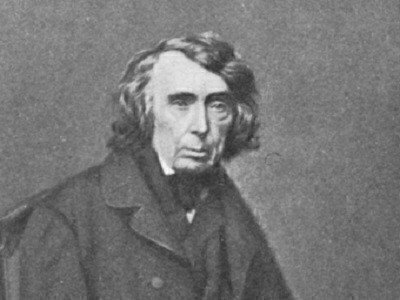

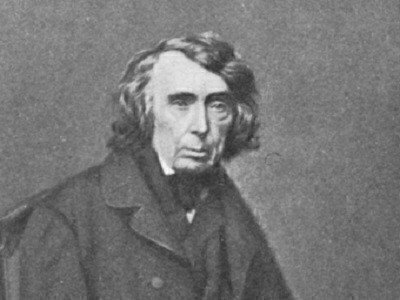

On May 28, 1861, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney directly challenged President Abraham Lincoln’s wartime suspension of the great writ of habeas corpus, in a national constitutional showdown.

Lincon and Taney had not been on good terms prior to Taney’s decision on the habeas question in Ex Parte Merryman, which he issued while acting as a circuit judge. Taney had also written the majority opinion in the controversial Dred Scott case in 1857, a decision than Lincoln publicly criticized in his famous debates with Stephen Douglas. Lincoln also made the Dred Scott decision a central theme of his 1860 presidential campaign.

As Chief Justice, Taney was forced to issue the presidential oath to Lincoln in March 1861, and to listen to Lincoln’s inaugural address, where he again criticized Taney and the Dred Scott decision, but not directly by name.

“The candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made in ordinary litigation between parties in personal actions the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal,” Lincoln said.

About three months later, Taney had his chance to address Lincoln’s vision of executive power in Ex Parte Merryman.

Article 1, Section 9, of the Constitution states that “the Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” The Great Writ’s origins go back to the signing of the Magna Carta in England in 1215 and the writ compels the government to show cause to a judge for the arrest or detention of a person.

After the start of the Civil War, President Lincoln ordered General Winfield Scott to suspend habeas corpus near railroad lines that connected Philadelphia to Washington, amid fears of a rebellion in Maryland that would endanger Washington.

On May 25, 1861, federal troops arrested a Maryland planter, John Merryman, on suspicion that he was involved in a conspiracy as part of an armed secessionist group. Merryman was detained at Fort McHenry without a warrant. Merryman’s attorney petitioned the U.S. Circuit Court for Maryland, which Taney oversaw, for his client’s release.

On May 26, Taney issued a writ of habeas corpus and ordered General George Cadwalader, Fort McHenry’s commander, to appear in the circuit courtroom along with Merryman and to explain his reasons for detaining Merryman.

Cadwalader didn’t comply with the writ and instead sent a letter back to Taney on May 27 explaining that Lincoln had authorized military officers to suspend the writ when they felt there were public safety concerns. Taney then tried to notify Cadwalader that he was in contempt of court, but soldiers at Fort McHenry refused the notice.

On May 28, Taney issued an oral opinion, which was followed by a written opinion a few days later. He stated that the Constitution clearly intended for Congress, and not the President, to have to power to suspend the writ during emergencies.

“The clause in the Constitution which authorizes the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is in the ninth section of the first article. This article is devoted to the Legislative Department of the United States, and has not the slightest reference to the Executive Department,” Taney argued. “I can see no ground whatever for supposing that the President in any emergency or in any state of things can authorize the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, or arrest a citizen except in aid of the judicial power,” Taney concluded.

However, Taney noted that he didn’t have the physical power to enforce the writ in this case because of the nature of the conflict at hand. “I have exercised all the power which the Constitution and laws confer on me, but that power has been resisted by a force too strong for me to overcome,” he said. But Taney did order that a copy of his opinion be sent directly to President Lincoln.

Lincoln didn’t respond directly or immediately to the Ex Parte Merryman decision. Instead, he waited until a July 4th address to confront Taney at a special session of Congress.

“Soon after the first call for militia it was considered a duty to authorize the Commanding General in proper cases, according to his discretion, to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, or, in other words, to arrest and detain without resort to the ordinary processes and forms of law such individuals as he might deem dangerous to the public safety,” Lincoln said. “This authority has purposely been exercised but very sparingly.”

Lincoln then presented his famous response to Taney. “Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the Government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated? Even in such a case, would not the official oath be broken if the Government should be overthrown when it was believed that disregarding the single law would tend to preserve it?”

The President also confronted Taney’s opinion that only Congress could suspend the writ.

“Now it is insisted that Congress, and not the Executive, is vested with this power; but the Constitution itself is silent as to which or who is to exercise the power; and as the provision was plainly made for a dangerous emergency, it can not be believed the framers of the instrument intended that in every case the danger should run its course until Congress could be called together, the very assembling of which might be prevented, as was intended in this case, by the rebellion,” Lincoln argued.

After the Merryman incident, Lincoln suspended the writ in other situations, and he received approval from Congress in March 1863 to suspend the writ for the duration of the conflict when “the public safety may require it.”

Lincoln and Taney’s great writ showdown

May 28, 2023 | by Scott BomboyOn May 28, 1861, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney directly challenged President Abraham Lincoln’s wartime suspension of the great writ of habeas corpus, in a national constitutional showdown.

Lincon and Taney had not been on good terms prior to Taney’s decision on the habeas question in Ex Parte Merryman, which he issued while acting as a circuit judge. Taney had also written the majority opinion in the controversial Dred Scott case in 1857, a decision than Lincoln publicly criticized in his famous debates with Stephen Douglas. Lincoln also made the Dred Scott decision a central theme of his 1860 presidential campaign.

As Chief Justice, Taney was forced to issue the presidential oath to Lincoln in March 1861, and to listen to Lincoln’s inaugural address, where he again criticized Taney and the Dred Scott decision, but not directly by name.

“The candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made in ordinary litigation between parties in personal actions the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal,” Lincoln said.

About three months later, Taney had his chance to address Lincoln’s vision of executive power in Ex Parte Merryman.

Article 1, Section 9, of the Constitution states that “the Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” The Great Writ’s origins go back to the signing of the Magna Carta in England in 1215 and the writ compels the government to show cause to a judge for the arrest or detention of a person.

After the start of the Civil War, President Lincoln ordered General Winfield Scott to suspend habeas corpus near railroad lines that connected Philadelphia to Washington, amid fears of a rebellion in Maryland that would endanger Washington.

On May 25, 1861, federal troops arrested a Maryland planter, John Merryman, on suspicion that he was involved in a conspiracy as part of an armed secessionist group. Merryman was detained at Fort McHenry without a warrant. Merryman’s attorney petitioned the U.S. Circuit Court for Maryland, which Taney oversaw, for his client’s release.

On May 26, Taney issued a writ of habeas corpus and ordered General George Cadwalader, Fort McHenry’s commander, to appear in the circuit courtroom along with Merryman and to explain his reasons for detaining Merryman.

Cadwalader didn’t comply with the writ and instead sent a letter back to Taney on May 27 explaining that Lincoln had authorized military officers to suspend the writ when they felt there were public safety concerns. Taney then tried to notify Cadwalader that he was in contempt of court, but soldiers at Fort McHenry refused the notice.

On May 28, Taney issued an oral opinion, which was followed by a written opinion a few days later. He stated that the Constitution clearly intended for Congress, and not the President, to have to power to suspend the writ during emergencies.

“The clause in the Constitution which authorizes the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is in the ninth section of the first article. This article is devoted to the Legislative Department of the United States, and has not the slightest reference to the Executive Department,” Taney argued. “I can see no ground whatever for supposing that the President in any emergency or in any state of things can authorize the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, or arrest a citizen except in aid of the judicial power,” Taney concluded.

However, Taney noted that he didn’t have the physical power to enforce the writ in this case because of the nature of the conflict at hand. “I have exercised all the power which the Constitution and laws confer on me, but that power has been resisted by a force too strong for me to overcome,” he said. But Taney did order that a copy of his opinion be sent directly to President Lincoln.

Lincoln didn’t respond directly or immediately to the Ex Parte Merryman decision. Instead, he waited until a July 4th address to confront Taney at a special session of Congress.

“Soon after the first call for militia it was considered a duty to authorize the Commanding General in proper cases, according to his discretion, to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, or, in other words, to arrest and detain without resort to the ordinary processes and forms of law such individuals as he might deem dangerous to the public safety,” Lincoln said. “This authority has purposely been exercised but very sparingly.”

Lincoln then presented his famous response to Taney. “Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the Government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated? Even in such a case, would not the official oath be broken if the Government should be overthrown when it was believed that disregarding the single law would tend to preserve it?”

The President also confronted Taney’s opinion that only Congress could suspend the writ.

“Now it is insisted that Congress, and not the Executive, is vested with this power; but the Constitution itself is silent as to which or who is to exercise the power; and as the provision was plainly made for a dangerous emergency, it can not be believed the framers of the instrument intended that in every case the danger should run its course until Congress could be called together, the very assembling of which might be prevented, as was intended in this case, by the rebellion,” Lincoln argued.

After the Merryman incident, Lincoln suspended the writ in other situations, and he received approval from Congress in March 1863 to suspend the writ for the duration of the conflict when “the public safety may require it.”

Lincoln and Taney’s great writ showdown | Constitution Center

On May 28, 1861, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney directly challenged President Abraham Lincoln’s wartime suspension of the great writ of habeas corpus, in a national constitutional showdown.

constitutioncenter.org

gtyellowjacket

Iconic Member

- Messages

- 2,413

Ugh. Ignoring a lawful judicial order. Disregarding the separation of powers. Wiping his gaunt posterior with the constitution. And his supporters don't give a damn. Reminds me of a much more modern president, ignoring the gaunt posterior part.Re: Lincoln and writ of Habeas Corpus

Lincoln and Taney’s great writ showdown

May 28, 2023 | by Scott Bomboy

On May 28, 1861, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney directly challenged President Abraham Lincoln’s wartime suspension of the great writ of habeas corpus, in a national constitutional showdown.

Lincon and Taney had not been on good terms prior to Taney’s decision on the habeas question in Ex Parte Merryman, which he issued while acting as a circuit judge. Taney had also written the majority opinion in the controversial Dred Scott case in 1857, a decision than Lincoln publicly criticized in his famous debates with Stephen Douglas. Lincoln also made the Dred Scott decision a central theme of his 1860 presidential campaign.

As Chief Justice, Taney was forced to issue the presidential oath to Lincoln in March 1861, and to listen to Lincoln’s inaugural address, where he again criticized Taney and the Dred Scott decision, but not directly by name.

“The candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made in ordinary litigation between parties in personal actions the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal,” Lincoln said.

About three months later, Taney had his chance to address Lincoln’s vision of executive power in Ex Parte Merryman.

Article 1, Section 9, of the Constitution states that “the Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” The Great Writ’s origins go back to the signing of the Magna Carta in England in 1215 and the writ compels the government to show cause to a judge for the arrest or detention of a person.

After the start of the Civil War, President Lincoln ordered General Winfield Scott to suspend habeas corpus near railroad lines that connected Philadelphia to Washington, amid fears of a rebellion in Maryland that would endanger Washington.

On May 25, 1861, federal troops arrested a Maryland planter, John Merryman, on suspicion that he was involved in a conspiracy as part of an armed secessionist group. Merryman was detained at Fort McHenry without a warrant. Merryman’s attorney petitioned the U.S. Circuit Court for Maryland, which Taney oversaw, for his client’s release.

On May 26, Taney issued a writ of habeas corpus and ordered General George Cadwalader, Fort McHenry’s commander, to appear in the circuit courtroom along with Merryman and to explain his reasons for detaining Merryman.

Cadwalader didn’t comply with the writ and instead sent a letter back to Taney on May 27 explaining that Lincoln had authorized military officers to suspend the writ when they felt there were public safety concerns. Taney then tried to notify Cadwalader that he was in contempt of court, but soldiers at Fort McHenry refused the notice.

On May 28, Taney issued an oral opinion, which was followed by a written opinion a few days later. He stated that the Constitution clearly intended for Congress, and not the President, to have to power to suspend the writ during emergencies.

“The clause in the Constitution which authorizes the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is in the ninth section of the first article. This article is devoted to the Legislative Department of the United States, and has not the slightest reference to the Executive Department,” Taney argued. “I can see no ground whatever for supposing that the President in any emergency or in any state of things can authorize the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, or arrest a citizen except in aid of the judicial power,” Taney concluded.

However, Taney noted that he didn’t have the physical power to enforce the writ in this case because of the nature of the conflict at hand. “I have exercised all the power which the Constitution and laws confer on me, but that power has been resisted by a force too strong for me to overcome,” he said. But Taney did order that a copy of his opinion be sent directly to President Lincoln.

Lincoln didn’t respond directly or immediately to the Ex Parte Merryman decision. Instead, he waited until a July 4th address to confront Taney at a special session of Congress.

“Soon after the first call for militia it was considered a duty to authorize the Commanding General in proper cases, according to his discretion, to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, or, in other words, to arrest and detain without resort to the ordinary processes and forms of law such individuals as he might deem dangerous to the public safety,” Lincoln said. “This authority has purposely been exercised but very sparingly.”

Lincoln then presented his famous response to Taney. “Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the Government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated? Even in such a case, would not the official oath be broken if the Government should be overthrown when it was believed that disregarding the single law would tend to preserve it?”

The President also confronted Taney’s opinion that only Congress could suspend the writ.

“Now it is insisted that Congress, and not the Executive, is vested with this power; but the Constitution itself is silent as to which or who is to exercise the power; and as the provision was plainly made for a dangerous emergency, it can not be believed the framers of the instrument intended that in every case the danger should run its course until Congress could be called together, the very assembling of which might be prevented, as was intended in this case, by the rebellion,” Lincoln argued.

After the Merryman incident, Lincoln suspended the writ in other situations, and he received approval from Congress in March 1863 to suspend the writ for the duration of the conflict when “the public safety may require it.”

Lincoln and Taney’s great writ showdown | Constitution Center

On May 28, 1861, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney directly challenged President Abraham Lincoln’s wartime suspension of the great writ of habeas corpus, in a national constitutional showdown.constitutioncenter.org

superrific

Master of the ZZLverse

- Messages

- 10,641

If you think Lincoln is a bad president, that's your prerogative. You won't find anyone to agree with you, but that's evidently unimportant to you. Also, FYI, the Taney order in Merryman was not at all lawful. It was sort of an in-chambers opinion that was never referred to the full court; Taney himself was conflicted and should have recused or resigned; and oh yeah, Taney sympathized with the Confederacy and was not loyal to the union.Ugh. Ignoring a lawful judicial order. Disregarding the separation of powers. Wiping his gaunt posterior with the constitution. And his supporters don't give a damn. Reminds me of a much more modern president, ignoring the gaunt posterior part.

Comparing Trump and Lincoln approvingly is so abjectly stupid as to be worth no further response and you won't get one from me, and hopefully nobody else.

uncjhodges

Distinguished Member

- Messages

- 483

I would say not finding anyone that agrees with him is very important to himIf you think Lincoln is a bad president, that's your prerogative. You won't find anyone to agree with you, but that's evidently unimportant to you.

ChapelHillSooner

Iconic Member

- Messages

- 1,124

That made me google how many pull-ups Hegseth can do.

"The challenge involved completing 50 pull-ups and 100 push-ups within 10 minutes. Hegseth and Kennedy Jr. both successfully completed the challenge"

I was expecting to hear that he could do X pull-ups in one go. Doing 50 pull-ups and 100 push-ups in 10 minutes isn't exactly something to write home about.

superrific

Master of the ZZLverse

- Messages

- 10,641

Do you get to do the pullups hands facing in? I.e. can your biceps help?That made me google how many pull-ups Hegseth can do.

"The challenge involved completing 50 pull-ups and 100 push-ups within 10 minutes. Hegseth and Kennedy Jr. both successfully completed the challenge"

I was expecting to hear that he could do X pull-ups in one go. Doing 50 pull-ups and 100 push-ups in 10 minutes isn't exactly something to write home about.

If so, I could probably do 20 pullups in 10 minutes, and 15 pushups. If no hands facing, then zero pullups. It's true that I'm out of shape and was never a hulking physical presence in the first place, but 50 pull-ups and 100 pushups isn't nothing.

Share: