Once you start to explain corruption as cultural rather than institutional, you stop analyzing political economy and start pathologizing entire societies. That also conveniently erases the role of sanctions, capital flight, and external pressure. Somehow, this logic only ever gets applied to countries on the receiving end of U.S. power.

This is not true. The US does not have a culture of corruption that rivals other places on Earth. The US does have a culture of racial scapegoating; it doesn't pathologize the US to take note of that.

A lot of it -- perhaps the vast majority -- is historical. Communist economies like North Korea or the Soviet Union run on bribes. There are other places where bribes have become routinized, as in donbosco's Paraguay example. When bribes are considered a natural part of life, then it's hard to eliminate them.

For instance, suppose you were born in North Korea. The North Korean economy runs on bribes. So much so that I doubt North Koreans think it's wrong. But in any event, nobody in North Korea today knows how to run a society without bribes, because they have never seen one. Their parents didn't see one. Their grandparents never saw one. There is no lived historical memory at all of a society without endemic corruption. So if we got rid of Kim Jong Un and put in a democracy, what's going to happen? Everyone will be taking bribes.

This is the story of India/Pakistan. Both are democracies; both are tremendously corrupt. It's not because Indian people are corrupt. It's because certain things are just taken for granted. My ex-wife was born in India, and her father at one point had a successful trucking business alongside a job at Firestone or some place like that. Her father is a moral person. He was honest in all his dealings with me, and in his effort to set up a jewelry business in Toronto (which didn't do well, perhaps because he was honest). But in his India business, he took bribes.

And that bribe income created "black money" for him (i.e. investments under the table), which was a problem when moving to the US. The problem wasn't simply that it was under the table. If that was the problem, he could have taken advantage of the many "come clean" programs from the Indian government over the years. The problem was that it was a joint investment business. There were like two dozen people who had invested their bribe money together, and he couldn't just extract his share without exposing the rest, who did not want to be exposed. And the fact that there were two dozen people involved is telling. It was so common.

One reason that corruption is hard to root out is that it's often bidirectional. My ex-FIL would tell me (using coded language to avoid admitting outright what he was doing, but that was a matter of politeness more than anything; he knew I knew what he was talking about) that he would take bribes because he would have to pay them. And the people paying him the bribes are probably taking bribes for the same reason.

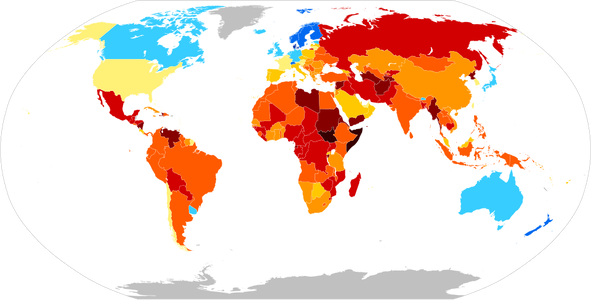

So in my view, there absolutely are cultures of more or less corruption. It's not because the people are somehow bad; it's that history pushed the societies into a corruption system and it's very hard to break out of such things. Reining in corruption is a huge collective action problem

www.reuters.com